1Department of Economics, College of Arts & Commerce Andhra University, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

This article explores the influence of remittances on economic development in the region, focusing on their effects on savings (SAV), remittance inflows, the monetary base and overall economic growth from 1998 to 2022. This study employs the system generalised method of moments to analyse the impact of remittances on economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). It examines the connection between remittances and important economic factors, such as real gross domestic product (RGDP), money supply (M2) and government expenditure (GEX). Through empirical analysis, it is found that remittances positively influence key economic indicators such as RGDP, money supply (IBM) and GEX. The results suggest that remittances contribute to enhancing domestic SAV and investment, thereby stimulating economic growth. The results emphasise the significance of remittances as a crucial source of external funding for Sub-Saharan African nations, showcasing their ability to promote sustainable development and alleviate poverty in the region.

Remittances, economic growth, system GMM analysis, Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Remittances are vital for the economic development of Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). At present, significant remittances in developing countries become a source of finance and bring economic growth and development through reducing household poverty and increasing consumption, and further building investment in both human and physical capital which results in less vulnerability from natural and economic shock (Ayana et al., 2023).

Over the last 20 years, remittance flows to developing countries have experienced substantial growth. Beginning at $96.5 billion in 2001, remittances jumped to $160 billion by 2004, marking a significant increase of 65% within just three years. This upward trajectory continued, with remittances reaching: $300 billion in 2007, a 50% rise from 2004 $372 billion in 2011, a 24% increase from 2007 $401 billion in 2012, a 5.3% rise from the previous year. By 2021, formal remittance channels alone recorded an impressive $589 billion, with additional amounts sent through informal means not included in this total. This steady growth underscores the vital role of remittances in supporting economic development in recipient countries.

Currently, remittances rank as the second-largest source of external financial flows to developing countries, following foreign aid, and have shown a steady upward trend over time (Eggoh et al., 2019). The rising volume of the flow of remittances into developing countries in recent years is attracting increasing attention because of their effect on the receiving countries. Ahortor and Adenutsi (2009) discovered that remittances positively influence the economic growth of SSA. Nevertheless, the impact of remittances on the economic growth of SSA remains a topic of ongoing debate. While some argue that remittances have a positive impact on economic growth in SSA, others have a more pessimistic view, claiming that remittances can create income inequalities and promote dependency. To examine the relationship between remittances and economic growth in SSA, a system GMM analysis was conducted (Eggoh et al., 2019). The study revealed that remittances positively influence both growth and investment in SSA, indicating that remittances can enhance the region’s overall economic growth. Jongwanich (2007) revealed that remittances hurt domestic savings (SAV). This indicates that remittances may be used for immediate consumption rather than being saved and invested in the domestic economy.

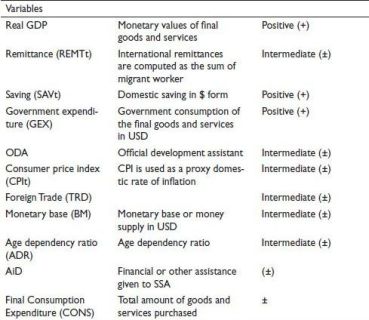

The study employed real gross domestic product (RGDP) as the dependent variable, with remittance inflow (RMIT), SAV, official development assistance (ODA) and government expenditure (GEX) as the explanatory variables. Additionally, the study considered the consumer price index (CPI), monetary base (M2), foreign trade (AiD), age dependency ratio (ADR) and final consumption expenditure (CONS) as controlled factors.

Overall, the analysis confirms that remittances significantly influence the economic growth of SSA. The findings of this study align with previous research, indicating that remittances positively impact economic growth in SSA. Additionally, the study highlights the importance of policies that encourage the productive use of remittances, such as investing in productive assets and projects that can generate long-term economic growth. Furthermore, the study emphasises the need for financial development and an improved institutional framework to fully harness the potential of remittances in driving economic growth in SSA. The study conducted a system GMM analysis to examine the impact of remittances on economic growth in SSA.

Review of Literature

Review of Theoretical Literature

The theoretical literature on remittances and economic growth in SSA offers insights into the mechanisms and channels through which remittances can influence the region. One important theoretical framework is the ‘investment channel’, which suggests that remittances can drive economic growth (Ahortor & Adenutsi, 2009).

Remittances to developing countries were projected to rise to $440 billion in 2014–2015, up from $414 billion in 2013, marking a 6.3% increase from 2012. This figure exceeds the combined total of ODA and foreign direct investment received by these countries, with the exception of China. Recently, there has been a shift towards ‘South–South’ migration, with over 50% of emigrants from developing countries moving to other developing countries within the same region (Rao, 2016).

Over the past decade, remittances to developing countries have more than doubled. However, growth in Africa, particularly SSA, has been slow. For instance, SSA received $1.86 billion of the $9 billion in remittances to Africa in 1990 and $5.96 billion of the $14 billion in 2003. Remittances to SSA reached $10 billion in 2005, peaked at $21.6 billion in 2008, and slightly declined to $20.7 billion in 2009 due to the global financial crisis.

SSA lags behind other regions in remittance flows. In 2009, SSA received $20.74 billion, significantly less than India ($49.26 billion), China ($47.55 billion) and Mexico ($22.16 billion). Despite lower remittances in absolute and per capita terms, SSA countries are among the largest recipients when remittances are viewed relative to GDP, serving as a crucial source of foreign exchange for some countries.

According to classical theory, massive capital inflows and industrialisation will boost economic growth and modernisation. Migrants are seen as agents of change in developing countries, and they actively promote migration because it accelerates investment and increases exposure to rational, democratic ideas, modern knowledge and education.

Structural and dependency theories argue that migration heightens dependence on global political-economic systems controlled by powerful Western states. It is believed that traditional peasant societies have been devastated by migration, as it disrupts their economies and displaces their populations. Migration is seen as detrimental to the economies of developing countries and is considered a primary factor in the ‘development of underdevelopment’ (de Haas, 2021).

Social network theory posits that remitters are aware of social relationships in addition to economic factors when sending money. They remit for several reasons: first, the transfer might be reciprocal, as migrants build social obligations with those they send money to, often in the form of child care or goods with traditional or sentimental value. Second, migrants may remit to adhere to moral values learned within their community. Lastly, remitters enhance their social visibility in both the sending and receiving countries and avoid social group sanctions by remitting (Vonneilich, 2022).

The literature on the welfare-improving benefits of recipient remittances dates back to the 20th century. At the micro level, migration is viewed as a process that contributes to the optimal allocation of production factors for the benefit of all, according to the 1960s neoclassical approach (Haas, 2007). According to this theory, once wage levels are equal at both the origin and destination, the process of factor price equalisation will result in migration ceasing. According to this viewpoint, reallocating labour from rural, agricultural areas to urban, industrial sectors is necessary for economic growth (Alok & Mishra, 2022).

On the other hand, according to Neo-Marxist theory migration and remittance reinforce the capitalist system and exacerbate inequality in one country. Migration and remittance were seen as harmful as exposure to the prosperity of migrant families which led to an increase in the demand for foreign products.

Empirical Review

It was discovered that remittances have a positive and significant impact on economic growth by increasing real private investment and fixed capital accumulation, which increases capital accumulation, reduces the current account deficit and external debt burden, and improves household education/skills by improving human capital. This study’s findings suggest that international labour migration has significant potential benefits for poor people in developing countries like Ethiopia (Eggoh et al., 2019; Yaekob, 2016).

Remittances can provide households with additional income, which can be used for investment in housing, businesses, education and healthcare (Kratou & Gazdar, 2015) by using GMM in SSA. This increased investment can lead to job creation, productivity improvements and overall economic growth. Overall, the literature suggests that remittances can have a positive impact on economic growth in SSA. However, the impact of remittances on economic growth in SSA is not without challenges and limitations.

The relationship between migrant remittances and economic growth through the financial development channel can be explained in two different ways. On the one hand, the smooth functioning of financial markets, which reduces transaction costs, can help to direct remittances to projects that produce the highest profit and thus increase growth rates (Ahortor & Adenutsi, 2009).

To address the endogeneity issue, the researchers applied the GMM method to estimate the relationship between workers’ remittances, economic growth and poverty in developing Asia and Pacific countries (Table 1). The empirical evidence suggests that remittances only have a marginal impact on growth operating through domestic investment and capital development (Eggoh et al., 2019).

Table 1. Overview of the Literature on the Relationship Between Remittances and Economic Growth.

.jpg/10_1177_22297561241291274-table1(1)__400x1043.jpg)

Note: GMM stands for Generalised Method of Moments, SGMM: System Generalised Method of Moments FEM: Fixed effect Model, REM: Random effect Model and SIDS: Small Island Developing States.

Methods and Discussions

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical framework established by Kwabena et al. (2020), referencing Solow (1995), is grounded in the Solow long-run growth model, originally developed by Robert Solow in 1956. This model elucidates the mechanisms of economic growth over an extended period by integrating three critical factors: capital accumulation, population growth and technological advancement. Utilising the Cobb–Douglas production function, financial inflows can significantly influence economic growth through various mechanisms. RMITs play a crucial role in enhancing growth by increasing the capital stock. Specifically, remittances, along with domestic SAV, contribute to long-term investments that bolster physical capital (K) (Ribaj & Mexhuani, 2021).

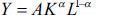

The Solow model can be mathematically represented through a Cobb–Douglas production function, which captures the relationship between output (Y), capital (K) and labour (L)

(1)

(1)

Whereas

A represents total factor productivity,

α indicates the output elasticity of capital (with 0<α<10<α<1).

This function illustrates how output is generated from varying levels of capital and labour, moderated by technological efficiency.

Estimation Technique and Empirical Model

Several techniques have been employed to assess the impact of financial inflows on economic growth. While Zahonogo (2017) used the Pooled Mean Group Estimation Technique used PMG/MG-ARDL framework (Gashu, 2021) used different generalised moment methods (DGMM). However, the unique properties of this study used instrumental variable system generalise moment method (SGMM), which is more efficient and robust than others.

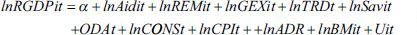

According to neoclassical economic growth theories, the relationship between economic growth and remittances can be expressed by applying natural logarithms to both sides, as illustrated below.

(2)

(2)

whereas

lnRGDP represents the natural logarithm of RGDP, lnGEX denotes the natural logarithm of government spending on education, lnAID refers to the natural logarithm of foreign aid, lnREMT indicates the natural logarithm of remittance flows to SSA, lnTRD is the natural logarithm of trade, lnSav represents the natural logarithm of SAV, ODA stands for official development assistance, lnCONS refers to the natural logarithm of consumption, BM signifies the monetary base or money supply, ADR denotes the age dependency ratio and Uit is the error term.

Panel Unit Root Tests

The dataset in this study spans 24 years, creating a time series longer than 20 years, which means the presence of unit roots in the variables cannot be ruled out. When the time dimension exceeds 20 years, it is recommended to use macro panel estimation techniques. To confirm the presence of a unit root, three distinct and widely used tests are employed: Im-Pesaran-Shin test: This test allows for heterogeneous autoregressive parameters across (Yusheng et al., 2021) panels, and the number of panels and periods are both large. It is suitable for unbalanced panels with fixed effects and time trends (Salazar, 2012).

Fisher-type test: This test combines the p values of individual unit root tests for each panel, using either the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) or the PP test. It allows for heterogeneous autoregressive parameters across panels, and the number of panels and periods are both large. It is suitable for unbalance (Cyntia ROSA DEWI, 2002).

GMM Specification

We use dynamic panel data estimators (difference GMM and system GMM) developed to properly test the hypothesis that remittances can affect economic growth (Arellano & Bond, 1991; Góes, 2016) to develop our growth model. The difference GMM estimator is calculated by transforming all repressors, typically by differencing, whereas the system GMM model is composed of stacked regressions in levels and differences (Roodman, 2009). The baseline regression for the system GMM specification is

.jpg) (3)

(3)

Whereas is the dependent variable for individual i at time t.

is a lagged dependent variable, which captures the dynamic aspect of the model.

and are independent variables (explanatory variables) for individual i at the time

β and ¥ are coefficients for the independent variables,λi is an unobserved country – specific effect, μt is a time-specific effect and εit is the error term.

The GMM specifications include the same covariates as before, while the interaction term demonstrates a change in the behaviour of financial development effects after some structural breaks. This specification allows us to assess whether the threshold variable qit becomes more or less

While the lagged levels of the exogenous variables are used as instruments in the difference GMM model, the GMM system estimator uses lagged differences of the explanatory variables as instruments for equations in levels, as well as lagged levels of the explanatory variables as instruments for equations in first differences. These models have been widely used to address the endogeneity issue that arises in the estimation of growth regressions using panel data (Arellano & Markman, 1995; Blundell & Bond, 1998). They also account for biases caused by country-specific effects or the presence of initial GDP in the growth covariates. Finally, as discussed in the preceding studies, GMM avoids simultaneity and reverses causality issues. To ensure the consistency of the GMM estimators, two diagnostic tests are run: Hansen’s test for over-identifying restrictions, where the null hypothesis is that the instruments are not correlated with the residuals, and Arellano–Bond’s test for second-order correlation in the first differenced residuals.

The system GMM estimator is robust to various forms of heteroscedasticity and serial correlation (Góes, 2016; Roodman, 2009).

Data and Measurement

Table 2 presents comprehensive descriptions of the variables, their anticipated signs and the rationale for their inclusion in our study. Our research examines 17 countries in SSA from 1998 to 2022, selected based on the availability of remittance data during this timeframe. We collected data on various indicators, including RGDP, SAV, CPI, ODA, remittances, ADR, monetary base, trade and AiD, using the World Development Indicators (WDI) database (World Bank, 2023) as a source. For data analysis, we employed the Stata 15.0 statistical software. By utilising the robust command in Stata along with the system GMM approach, we effectively addressed issues related to heterogeneity and endogeneity in our analysis. Additionally, we conducted several diagnostic tests to validate our variables and ensure the reliability of our findings.

Table 2. Definition, Measurement and Expected Sign of Variables.

Results and Discussions

In this section, we present the results of our estimations and conduct a comparative analysis. We commence by examining the summary statistics of the variables, followed by an exploration of the results from the stationarity test. Next, we present the results of the SGMM and discuss potential explanations for the observed outcomes

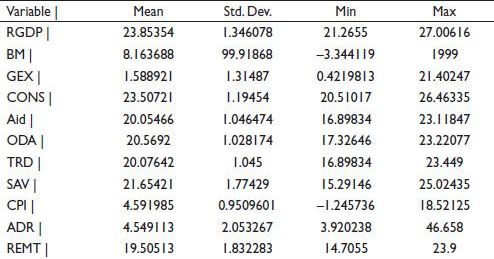

Summary of Statistics

The summary statistics from Table 3 provide valuable insights for the countries under consideration: The mean RGDP during the specified period is approximately $23.85 billion, with a standard deviation of $1.34 billion, Money supply (IBM) has an average value of $8.16 billion, accompanied by a standard deviation of $9.9 billion, GEX averages at 1.5, with a standard deviation of 1.3, aggregate consumption (CONS) has an average of 23.5, with a standard deviation of 1.19, foreign aid (AiD) exhibits an average value of $20.05 billion, with a standard deviation of 1.046, remittances (REMT) show a mean value of $19.56 billion, with a standard deviation of $1.83 billion, trade has an average of 20.07, with a standard deviation of 1.045, domestic saving averages at 21.64, with a standard deviation of 1.77, the CPI, which serves as a proxy for inflation, has an average of 4.51, with a standard deviation of 0.95, the ADR has an average of 4.51, with a standard deviation of 0.5, Overseas Development Assistance (ODA), on the other hand, has a standard deviation of $20.56 billion and a mean value of $0.763 billion, Interestingly, the table suggests that ODA outperformed RMITs to SSA, with a minimum value of $17.32 billion, while remittances minimum value of $14.77 billion.

Table 3. Summary of Statistics.

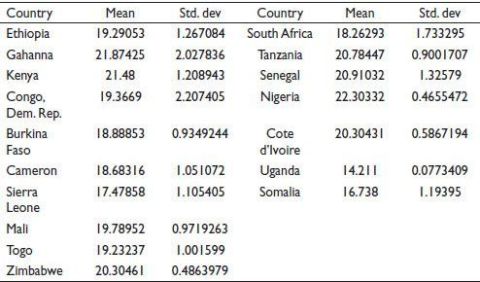

As shown in Table 4, Nigeria, Ghana and Kenya lead the list of countries with the highest average remittance values, recorded at 22.302, 21.87 and 21.48, respectively. This implies that sample countries that have the highest remittance receipt have with somewhat small amount of variation. On the other hand, Uganda, Somalia and Sierra Leone are found to have the lowest mean value of remittance with 14.21, 16.73 and 17.47, respectively.

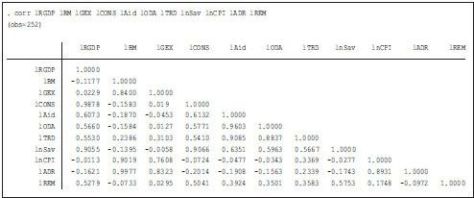

Appendix A presents the correlation matrix of the study. From the result, we observed that remittance has a positive correlation with real GDP of SSA Africa. The correlation coefficient is 0.529, indicating that remittance is marginally correlated to real GDP during the study period under consideration. The correlation matrix result has also indicated that SAV and aggregate consumption (CONS) are positively and strongly correlated with real GDP. It is also observed from Appendix A that monetary base (BM), inflation (CPI) and ADR have a negative, but weak correlation with real GDP (RDGP). The positive correlation of remittance received implies that the remittance receipt may adversely boost economic growth in SSA countries. The fact that there is a positive or negative correlation between remittance and economic growth enables us to investigate the magnitude by which remittance affects economic growth in SSA during the periods under consideration.

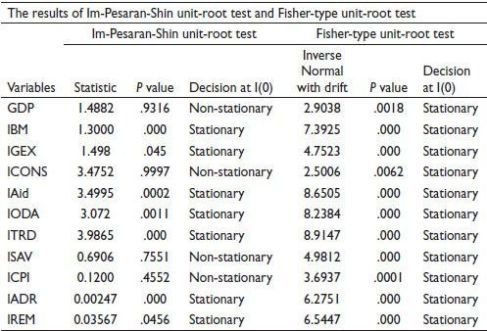

Stationary Test

To achieve effective and impartial estimation of panel data, conducting a stationarity test is essential. This test assesses whether the panel dataset shows unit-root characteristics or remains stationary, in accordance with Salazar’s (2012) recommendations. We employ two specific tests: the panel extension of Fisher’s ADF test and the Im-Pesaran-Shin test, both of which are appropriate for unbalanced panels that include fixed effects and time trends (Choi, 2001; Im et al., 2003). The null hypothesis for these tests posits that all panels are non-stationary, while the alternative hypothesis indicates that at least some panels are stationary. We reject the null hypothesis of non-stationarity if the p value equals zero; otherwise, we accept it. Our results from the ADF test (see Appendix B) reveal that 11 variables—RGDP, ODA, BM, trade, consumption, remittances, government final expenditure, ADR, inflation (PCI) and domestic investment—are stationary according to the Fisher-type test. However, in the case of the Im-Pesaran-Shin unit root test, RGDP, consumption, domestic SAV and inflation are not stationary at this level. Nevertheless, the remaining seven variables exhibit stationarity. Hence, there is evidence supporting the possibility that some panels are non-stationary, while we reject the null hypothesis that all panels exhibit non-stationarity. To address this issue, we turn to the GMM estimation technique.

Table 4. The Mean and Standard Deviation of Remittances Across Sub-Saharan Africa.

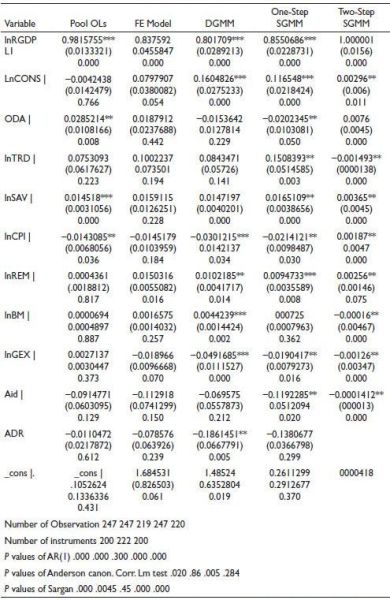

Table 5. Model Selection Process.

Note that: lnRGDPl1 means natural logarithm of real gross domestic product at lag one.

Empirical Results and Discussion

Model Selection Criteria

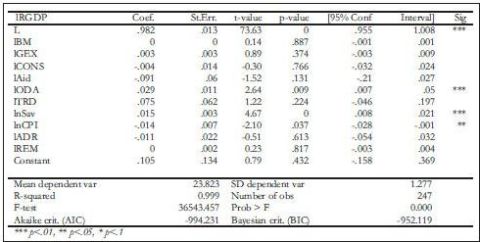

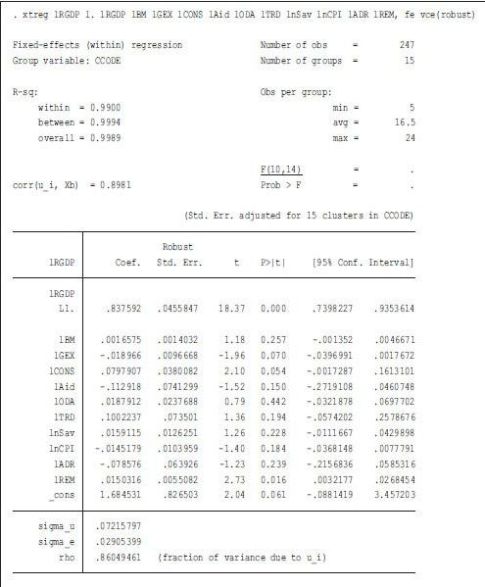

In the process of selecting a model, the heuristic approach suggests a series of steps: first, estimate the pool OLS; second, estimate the partial adjustment equation using fixed effects; third, estimate the differences GMM model; and finally, the decision is made by comparing the coefficients of lagged dependent variables. The outcome indicates that the system GMM model is chosen because its estimates are less than those from the fixed effects model (refer to Appendixes C–E) and Table 4.

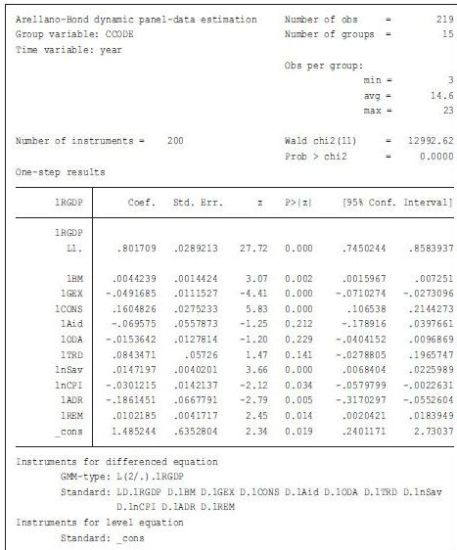

Table 5 presents the results from five distinct estimation models. The Anderson canon correlation LM test and the Sargan test both suggest the absence of autocorrelation and the validity of the instruments used. The Sargan test’s p values tend to enhance with the inclusion of more variables. Our analysis primarily centres on the full model, specifically the Mostly Two-Step system GMM, as both it and the one-step GMM were chosen. However, the two-step GMM is widely regarded as more precise and reliable compared to the one-step estimation method (Hwang & Sun, 2018).

Table 6. Five Different Estimation Results Dependent Variable: Large.

Note: *** significant at 95% level of confidence where as ** significant at 90 level of confidence.

Table 6 presents the results of the two-step GMM model, which indicates that remittances remain positively significant at a 5% level. A 1% increase in remittances results in a 0.0256% rise in economic growth, highlighting the positive influence of remittances on economic development. This impact is largely due to the dual role of remittances, which are utilised for both consumption and investment in profitable enterprises, thereby benefiting recipient families and the broader economy. This perspective is supported by various studies, including those by Eggoh et al. (2019). The observed positive relationship between remittances and economic growth in SSA indicates that remittances can play a crucial role in bridging the resource gap within the region. This gap is largely driven by disparities in SAV and investment patterns, as well as imbalances in demand and supply. By leveraging remittances, SSA countries can potentially offset these deficiencies and foster sustainable economic growth.

The empirical results indicate that final consumption plays a significant and positive role in promoting economic growth. Specifically, a 1% increase in final consumption results in a 0.00296% rise in economic growth when employing the two-step system GMM, and a 0.1165% increase when using the one-step GMM. This notable effect can be linked to the influence of government consumption on economic expansion. An increase in government spending tends to boost employment, profitability and investment levels. This occurs because GEX generates multiplier effects on aggregate demand, thereby stimulating overall economic activity. The increased demand leads to higher production levels, as firms respond to the rise in demand by increasing output. This, in turn, creates a ripple effect throughout the economy, driving economic growth (History, 2021).

The findings from a single-step system GMM analysis indicate that Overseas Development Assistance (ODA) negatively impacts economic growth in SSA countries, with a coefficient of −0.0202345. This implies that a rise in ODA could lead to a 0.0202345% decrease in economic growth for SSA nations. These conclusions align with research by Kwabena et al. (2020). Possible reasons for this outcome include the low level of institutional quality in these countries, which fosters corruption and misdirects foreign inflows to unproductive areas, and the limited financial development in SSA. Over-borrowing by many developing countries, as noted by Sutradhar (2020), can also negatively influence growth. SSA countries are characterised by low financial development, ineffective macroeconomic policies and weak institutional quality.

In contrast, the robust estimate from a two-step system GMM reveals that ODA positively affects economic growth, with a coefficient of 0.0076, supported by Ayana et al. (2023) and Zardoub and Sboui (2023). This positive impact is attributed to the capital deficiency faced by poor developing countries due to low domestic SAV, limited access to capital markets and a narrow tax base. Foreign capital inflows can help mitigate these issues by addressing the deficit in capital stock and providing access to foreign markets with advanced technology and managerial expertise. This, in turn, contributes positively to sustainable economic growth.

The analysis using the two-step SGMM revealed a significant positive relationship between domestic SAV and economic growth in SSA. Specifically, a 1% increase in domestic SAV corresponds to an increase of 0.0036 in economic growth. This finding is consistent with research by Baldé (2011) as well as Eggoh et al. (2019), which emphasise the essential role of SAV in fostering growth and development. High levels of SAV contribute to various benefits, including enhanced political stability, capital accumulation, increased productivity, higher household and entrepreneurial incomes, timely pension disbursements, improved government tax revenues and resource allocation for future generations. The importance of assessing the level of SAV across the continent and its contribution to African economic growth.

The research findings indicate that inflation, as represented by the CPI, has a positive and significant impact on economic growth in SSA. Specifically, a 1% rise in inflation correlates with an increase of 0.00187 in the output of SSA countries. This conclusion is supported by studies conducted by Aizenman et al. (1990), which identified similar patterns within certain inflation thresholds.

The results from a two-step generalised method of moments (GMM) analysis reveal a significant negative correlation between trade, final GEX, the monetary base or money supply, and foreign aid with the economic output of SSA. Specifically, a 1% increase in trade is associated with a 0.1493% decrease in SSA’s economic growth. This correlation is consistent with previous studies, such as those by Corresponding (2012) and Zardoub and Sboui (2023), which suggests that the impact of trade on economic growth depends on whether the country’s resources are directed towards activities that contribute to long-term growth or away from them. This is based on endogenous growth models, which posit that the effectiveness of trade in driving economic growth varies based on the economy’s comparative advantage and the ability to adopt technologies from more advanced economies, often hampered by technological or financial constraints in less-developed countries.

Similarly, increases in final GEX, by 1%, are linked to a decrease in SSA’s economic growth by −0.00016%, a finding supported by Eggoh et al. (2019) and Kwabena et al. (2020). This negative relationship can be attributed to the crowding out effect, where government spending reduces the private sector’s capacity to invest, leading to decreased investment and, consequently, slowed economic growth.

An increase in the monetary base by 1% is associated with a decrease in SSA’s economic growth by 0.00016%, as confirmed by Feeny et al. (2014) and Abeka et al. (2021). This might be due to the influence of the US money supply on SSA’s economic growth, where a significant decrease in the money supply could lead to higher interest rates, potentially affecting SSA’s financial health and investment capacity, which in turn impacts economic growth.

Lastly, foreign aid negatively affects SSA’s economic growth by 0.00142% when it increases by 1%, as supported by Kwabena et al. (2020). This might be because foreign aid can provide immediate relief to SSA, but it may also have broader economic implications, such as increasing government debt, which could affect the overall economic growth of the country. Foreign aid can temporarily alleviate financial pressures on SSA but may not address underlying economic challenges that could impact long-term growth.

Conclusions

The study demonstrates the positive impact of remittances on economic growth in SSA. The findings highlight the significant role that remittances play in enhancing key economic indicators and fostering regional development. The study confirms that remittances significantly positively affect economic growth in SSA. The influx of remittances contributes to an increase in real GDP, which is crucial for the region’s economic development.

Remittances play a vital role in boosting domestic SAV. Households receiving remittances tend to save a portion of these funds, which can be channelled into productive investments, thereby fostering economic growth.

The findings indicate that remittances also positively influence GEX on public goods and services. This can lead to improved infrastructure, education and health services, which are essential for sustainable development.

The study highlights that the relationship between remittances and economic growth is not uniform across all countries. Less financially developed countries tend to benefit more from remittances, suggesting that the financial context plays a crucial role in determining the effectiveness of remittances in promoting growth.

It emphasises the importance of policies that promote the productive use of remittances and highlights the need for financial development and an improved institutional framework to maximise the benefits of remittances in driving economic growth in the region.

Governments and financial institutions should create incentives for remittance recipients to invest in productive ventures, such as small and medium-sized enterprises. This can be achieved through access to credit, training programmes and support services.

Appendix A. Correlation Matrix.

Appendix B. Unit Root Test.

Appendix C. POOL Ols.

Appendix D. Fixed Effect Adjustment Model.

Appendix E. Difference GMM Analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: The study was developed by Temesgen Yaekob Ergano and Prof. Sure Pula Rao, who established the research questions and objectives concerning the impact of remittances on economic growth in SSA. Methodology: Temesgen Yaekob Ergano was responsible for the research design and statistical analysis. Data Collection: Data was collected from the WDI database by both Temesgen Yaekob Ergano and Prof. Sure Pula Rao. Analysis: The data analysis was conducted using Stata 15.0 by Temesgen Yaekob Ergano and Prof. Sure Pula Rao. Writing: The original manuscript draft was prepared by Temesgen Yaekob Ergano, with revisions and final editing carried out by Prof. Sure Pula Rao. Supervision: Prof. Sure Pula Rao provided oversight and guidance throughout the research process.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the WDI database, maintained by the World Bank. The dataset includes various economic indicators relevant to the analysis of remittances and economic growth in SSA from 1998 to 2022. Access to the data can be obtained through the XML nested data at file:///C:/Users/DELL/Downloads/Journal%20Sen.xml

Additionally, any supplementary data or materials used in the analysis can be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Temesgen Yaekob Ergano  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0644-4636

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0644-4636

Abeka, M. J., Andoh, E., Gatsi, J. G., Kawor, S., Junior, M., Andoh, E., Gatsi, J. G., & Kawor, S. (2021). Financial development and economic growth nexus in SSA economies: The moderating role of telecommunication development. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2020. 1862395

Ahortor, C. R. K., & Adenutsi, D. E. (2009). The impact of remittances on economic growth in small-open developing economies. Journal of Applied Sciences, 9(18), 3275–3286. https://doi.org/10.3923/jas.2009.3275.3286

Aizenman, J., Jinjarak, Y., & Park, D. (1990). Capital flows and economic growth in the era of financial integration and crisis. http://www.nber.org/papers/w17502

Alok, P. J., & Mishra, K. (2022). Macroeconomic determinants of remittances to India. Economic Change and Restructuring, 55(2), 1229–1248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-021-09347-3

Arellano, C. M., & Markman, H. J. (1995). The managing affect and differences scale (MADS): A self-report measure assessing conflict management in couples. Journal of Family Psychology, 9(3), 319–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.9.3.319.1568522

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Ayana, I. D., Demissie, W. M., & Sore, A. G. (2023). Fiscal policy and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do governance indicators matter? PLoS One, 18, e0293188. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0293188

Baldé, Y. (2011). The impact of remittances and foreign aid on savings/investment in sub-Saharan Africa. African Development Review, 23(2), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8268.2011.00284.x

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

Corresponding, H. N. A. (2012). Financial development and economic growth in the UAE: Empirical assessment using ARDL approach to co-integration. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 4(5), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.5539/ijef.v4n5p105

Cyntia ROSA, DEWI. (2002). Picornavirus. Virus 52(1), 1–5.

de Haas, H. (2021). A theory of migration: The aspirations-capabilities framework. In Comparative migration studies (vol. 9, issue 1). Comparative Migration Studies. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4

Eggoh, J., Bangake, C., & Semedo, G. (2019). Do remittances spur economic growth? Evidence from developing countries. Journal of International Trade and Economic Development, 28(4), 391–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2019.

Feeny, S., Iamsiraroj, S., & McGillivray, M. (2014). Remittances and economic growth: Larger impacts in smaller countries? Journal of Development Studies, 50(8), 1055–1066. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.895815

Gashu, B. A. (2021). Impact of capital flow on economic growth in Ethiopia: Empirical evidence from (1980–2010) using ARDL approach. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-393202/v1

Góes, C. (2016). Institutions and growth: A GMM/IV panel VAR approach. Economics Letters, 138, 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2015.11.024

Haas, H. De. (2007). Remittances, migration and social development. United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

History, M. (2021). Impact of public consumption on economic growth. African Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 4(3), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.52589/AJESD

Hwang, J., & Sun, Y. (2018). Should we go one step further? An accurate comparison of one-step and two-step procedures in a generalized method of moments framework. Journal of Econometrics, 207(2), 381–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2018.07.006

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115(1), 53–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(03)00092-7

Jongwanich, J. (2007). Workers’ remittances, economic growth and poverty in developing Asia and the Pacific Countries [MPDD Working Paper Series WP/07/01]. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific.

Kratou, H., & Gazdar, K. (2015). Addressing the effect of workers’ remittance on economic growth: Evidence from MENA countries. International Journal of Social Economics, 43(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-08-2013-0189

Kwabena, T. D., Ebo, T. F., Frimpong, W. B., Antwi, D. S., & Kwabena, T. D. (2020). Do foreign financial inflows impact on economic growth? Evidence from sub-saharan Africa. Studies of Applied Economics, 38(2), 1–14.

Rao, N. (2016). The impact of remittances on economic growth in Ethiopia. Indian Journal of Commerce & Management Studies, 2, 1–15. http://www.scholarshub.net

Ribaj, A., & Mexhuani, F. (2021). The impact of savings on economic growth in a developing country (the case of Kosovo). Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 6, 1–13.

Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata Journal, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867x0900900106

Salazar. (2012). No Titleענף הקיווי: תמונת מצב. עלון הנוטע, 66(3), 37–39.

Sutradhar, S. R. (2020). The impact of remittances on economic growth in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. International Journal of Economic Policy Studies, 14(1), 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42495-020-00034-1

Vonneilich, N. (2022). Social relations, social capital, and social networks: A conceptual classification. In: A. Klärner, M. Gamper, S. Keim-Klärner, I. Moor, H. von der Lippe, & N. Vonneilich (Eds), Social networks and health inequalities (pp. 23–34). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97722-1_2

World Bank. (2023). Global economic prospects. World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1899-4

Yaekob, T. (2016). Relation of government expenditure with economic growth and poverty reduction in Ethiopian - ARDL analysis. International Journal of Current Research, 8(12), 43215–43221. https://www.journalcra.com/article/relation-government-expenditure-economic-growth-and-poverty-reduction-ethiopian-ardl

Yusheng, K., Bawuah, J., Nkwantabisa, A. O., Atuahene, S. O. O., & Djan, G. O. (2021). Financial development and economic growth: Empirical evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 26(3), 3396–3416. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.1967

Zahonogo, P. (2017). Trade and economic growth in developing countries: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Trade, 3(1/2), 41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joat.2017.02.001

Zardoub, A., & Sboui, F. (2023). Impact of foreign direct investment, remittances and official development assistance on economic growth: Panel data approach. PSU Research Review, 7(2), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-04-2020-0012