1Department of Peace and Conflict Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, Federal University, Oye, Ekiti, Nigeria

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The Niger Delta, Nigeria’s foremost oil-producing region, is caught in a profound paradox: immense hydrocarbon wealth coexists with acute water insecurity. This study investigates the complex interplay between extractive industries and the degradation of water resources, arguing that oil and gas operations have systematically undermined the region’s water sustainability. Through an analysis of oil spills, gas flaring and waste mismanagement, the article highlights how industrial pollution has disrupted aquatic ecosystems, contaminated drinking water sources and exacerbated health risks for local communities. Drawing on scholarly literature, the study critiques state complicity, regulatory failure and the inefficacy of remediation efforts particularly the underwhelming progress of the Ogoniland cleanup. It further explores the resistance strategies of affected communities and the limitations of existing institutional responses. By framing water access as both an ecological and political issue, the article calls for a justice-oriented approach to environmental governance in line with Sustainable Development Goal 6. The analysis concludes that without decisive policy reforms, community participation and strengthened accountability, the Niger Delta’s water crisis will persist as a symbol of resource-driven injustice.

Environmental justice, Nigeria, Niger Delta, oil exploitation, water sustainability

Introduction

In recent decades, the global drive for fossil fuel extraction has intensified ecological precarity in resource-rich but governance-poor regions. Nowhere is this more visible than in Nigeria’s Niger Delta, where the relentless pursuit of oil wealth has come at a devastating environmental cost. While the region plays a pivotal role in sustaining Nigeria’s economy, it simultaneously bears the brunt of toxic pollution, environmental degradation and social neglect (Gbadamosi & Aldstadt, 2025; Kodiya et al., 2025). Among the gravest consequences is the crisis of water sustainability, an unfolding tragedy in which rivers, streams and underground aquifers are increasingly rendered unsafe, inaccessible or extinct due to industrial activities. Oil spills, gas flaring and poorly managed waste disposal have transformed water from a source of life into a conduit of disease, displacement and death.

Although literature on the environmental impacts of oil exploitation in the Niger Delta is extensive (Bello & Nwaeke, 2023; Eweje, 2006; Ndinwa & Akpafun, 2012; Omokaro, 2024), much of it tends to generalise pollution as an unfortunate externality rather than a structural feature of Nigeria’s extractive economy. Such perspectives often overlook the political ecology of water, that is, how the control, contamination and commodification of water reflect deeper power asymmetries between the state, multinational oil corporations and marginalised local communities (Mbalisi & Nwaiwu, 2025). In this context, water scarcity is not merely the result of natural resource depletion but a manufactured condition rooted in state-corporate complicity, environmental injustice and regulatory failure.

The persistence of environmental hazards in the region is deeply tied to long-standing governance failures and the impunity enjoyed by oil companies. Despite numerous oil spills, flaring incidents and contamination reports, remediation efforts remain sporadic, opaque and largely symbolic. Regulatory agencies are underfunded or politically compromised, while oil companies often escape meaningful penalties through opaque legal settlements or outright denial (Agbakoba, 2025; Omokaro, 2024). Communities that demand compensation or cleanup face bureaucratic inertia or intimidation (Ogbu et al., 2024). These dynamics illustrate a broader pattern of environmental governance in Nigeria: one in which profit overrides protection, and affected populations are left to navigate a toxic terrain of survival with little recourse to justice or institutional accountability.

Despite the proliferation of global sustainability frameworks, most notably, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 6 (SDG 6), which seeks to ensure clean water and sanitation for all, little has changed on the ground (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2015). Equally, environmental, social and governance (ESG) policies adopted by some multinational corporations often lack binding accountability mechanisms and do not address local water sustainability needs in practice (Gbadamosi & Aldstadt, 2025). What remains underexplored is how communities in the Niger Delta contest, endure or adapt to the erosion of their water rights in the shadow of oil. This study seeks to fill that gap by interrogating the intersection of extractivism, environmental policy failure and grassroots resistance in the region. It argues that water insecurity in the Niger Delta is not simply a crisis of supply, but a symptom of deeper structural violence embedded in Nigeria’s petro-capitalist development trajectory.

This analysis also explores the potential for renewable energy development as an alternative to the current extractive model. Opportunities in solar, wind and mini-hydro projects have been identified in several Niger Delta communities, offering a pathway towards sustainable energy transitions that could mitigate ecological pressure on water systems.

The study is guided by two central questions:

This study makes three core contributions. First, it reframes water sustainability in the Niger Delta as a political struggle rooted in ecological injustice. Second, it highlights the systemic failures of state and corporate actors in safeguarding environmental rights. Third, it offers a grounded analysis of how affected communities are forging paths of resistance, resilience and recovery in the face of ecological collapse. The study unfolds through a thematic exploration, beginning with an analysis of the environmental impacts of oil extraction on water resources in the Niger Delta. This is followed by a critical examination of state complicity and the gaps in policy implementation that exacerbate water sustainability challenges. The study then highlights grassroots resistance movements, using spatial mapping to illustrate community activism and its significance in the broader struggle for environmental justice. The final sections offer policy recommendations aimed at aligning governance with SDGs, particularly SDG 6 on clean water and sanitation, culminating in a synthesis that ties together the key arguments presented.

Oil Wealth and Water Poverty: The Paradox of Extractive Development

The Niger Delta presents a stark paradox: while it generates over 90% of Nigeria’s export revenues through oil production (Ewim et al., 2023; Obiam & Amadi, 2022), it remains one of the most underdeveloped and ecologically devastated regions in the country. This contradiction underscores the central argument of this study: that Nigeria’s extractive development model, driven by petro-capitalism, is fundamentally incompatible with water sustainability, environmental justice and local livelihoods. Rather than fostering national prosperity, oil wealth has entrenched a form of petro-colonialism that privileges state and corporate interests over community survival (Ghazvinian, n.d.; Mbao & Osinibi, 2014).

The environmental toll of oil extraction in the region is most visible in the destruction of water systems. Decades of oil spills, gas flaring and industrial waste dumping have severely contaminated rivers, streams, wetlands and groundwater sources (Ukhurebor et al., 2021). Ogoniland, a symbol of this devastation, has reported hydrocarbon concentrations in drinking wells more than 900 times the World Health Organization (WHO)’s acceptable limits (Amnesty International & Centre for Environment, Human Rights and Development (CEHRD), 2012; United Nations Environment Programme, 2011). For many rural communities, these polluted waters are the only accessible sources for drinking, cooking and sanitation, creating a public health crisis marked by waterborne diseases, chronic illness and early mortality (Isukuru et al., 2024; Manetu & Karanja, 2021).

Gas flaring intensifies this crisis. Toxic emissions, including benzene, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, acidify water bodies and contaminate rainfall, undermining both human health and ecological systems (Elijah, 2022; Wami-Amadi, 2025). Despite international commitments under the Paris Agreement and SDGs, Nigeria remains among the top global gas-flaring nations (Ezinna et al., 2024). These emissions not only contribute to climate change but also exacerbate the degradation of water and soil, further endangering local agriculture and fisheries (Oishy et al., 2025).

While multinational oil companies such as Shell, Chevron and Eni publicly commit to environmental standards, their operational records in the Niger Delta tell a different story. Investigations and court rulings have documented patterns of negligence, misinformation and environmental harm (Amnesty International, 2018; Barry, 2010; United Nations Environment Programme, 2011). A landmark 2021 UK Supreme Court decision confirmed Shell’s liability for oil spills in Nigeria, validating long-standing community claims (Al Jazeera, 2021; Leigh Day, 2021). However, such legal victories remain largely symbolic, as enforcement mechanisms on the ground are fragmented, underfunded and vulnerable to political manipulation.

The Nigerian state’s complicity in this environmental crisis is structural. State institutions like the Department of Petroleum Resources (DPR) and the National Oil Spill Detection and Response Agency (NOSDRA) lack the autonomy, capacity and will to hold oil firms accountable (Akaakar, 2025; Sheriff et al., 2025). Instead of regulating extractive activities, these agencies often act as facilitators of impunity, suppressing evidence, delaying cleanup and enabling corporate misconduct. As Bamidele (2017) asserts, Nigeria’s petro-state has become dependent on environmental degradation, rendering the Niger Delta a ‘zone of sacrifice’ for national economic interests.

Despite rhetorical commitments to development, the extractive model has yielded little benefit for local populations. The Niger Delta records some of Nigeria’s worst human development indicators; high poverty, poor infrastructure, inadequate healthcare and youth unemployment (Ansari, 2024; Brisibe, 2024). Initiatives such as the Niger Delta Development Commission (NDDC) and the Ministry of Niger Delta Affairs are plagued by corruption, inefficiency and lack of transparency (Ojaduvba, 2025). Even the much-celebrated Hydrocarbon Pollution Remediation Project (HYPREP), mandated to implement UNEP’s Ogoni cleanup, has been marred by bureaucratic inertia and allegations of mismanagement (Yakubu, 2017).

Thus, the Niger Delta’s water crisis is not merely an environmental concern—it is a structural expression of extractive capitalism. The collusion between state actors and oil companies marginalises local voices and excludes communities from decisions that directly impact their access to safe water and environmental health. Clean water, in this context, becomes a casualty of petro-economic priorities and entrenched power asymmetries.

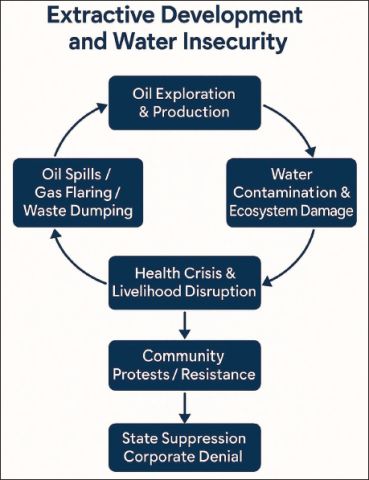

This dynamic is further illustrated in Figure 1, which presents a feedback loop demonstrating how extractive oil development in the Niger Delta perpetuates water insecurity, environmental degradation, and political suppression. As shown, the environmental destruction caused by oil spills and gas flaring leads to severe contamination of water sources, undermining community health and livelihoods. This environmental harm is compounded by weak governance and systemic political suppression, which hinder accountability and exacerbate local vulnerabilities. Over time, these interlinked processes reinforce each other, creating a vicious cycle that deepens socio-environmental injustices and entrenches the region’s ecological and political crises.

Figure 1. Feedback Loop Illustrating How Extractive Oil Development Perpetuates Water Insecurity, Environmental Degradation and Political Suppression in the Niger Delta.

Therefore, this section asserts that true water sustainability in the Niger Delta is unattainable under the prevailing oil-centric paradigm. What is required is a radical rethinking of development, one that prioritises ecological justice, enforces corporate accountability and centres community agency. Encouragingly, grassroots movements, civil society organisations and transnational networks are already mobilising to challenge extractive injustice and propose alternative governance models. The next section explores these forms of resistance and how they contribute to imagining a more just and sustainable future for the region.

Community Health and Ecological Justice: The Human Cost of Pollution

The environmental devastation wrought by oil extraction in the Niger Delta is not merely an ecological crisis. It is a full-blown public health emergency with far-reaching sociopolitical implications. Communities that once depended on rivers, streams and groundwater for drinking, farming and fishing now face chronic exposure to pollutants such as benzene, lead and hydrocarbons (United Nations Environment Programme, 2011). These substances infiltrate water bodies through recurring oil spills, illegal bunkering and unregulated industrial waste discharge, transforming once-vibrant ecosystems into toxic survival zones (Achunike, 2020; Ewim et al., 2023; Odubo & Odubo, 2024).

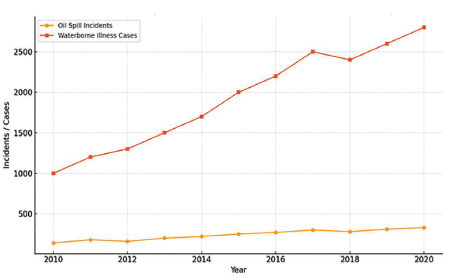

Figure 2. Correlation Between Oil Spills and Waterborne Illness in the Niger Delta (2010–2020).

Source: Adapted from public health and environmental reports.

As Figure 2 shows, there is a striking correlation between the frequency of oil spills and the rise in reported cases of waterborne diseases between 2010 and 2020. For instance, spikes in pollution during 2012, 2015 and 2018 corresponded with sharp increases in cholera and typhoid outbreaks, according to regional health surveillance data. This suggests a causal relationship between extractive activities and the deterioration of public health, particularly in rural and riverine areas where healthcare access is limited and water infrastructure is virtually non-existent (Hart, 2024; Nriagu, 2011).

What makes the situation especially unjust is the pattern of ‘environmental apartheid’, a term used to describe the unequal exposure of marginalised communities to environmental hazards. In the Niger Delta, this manifests in the systematic neglect of riverine populations who are forced to consume contaminated water, while urban elites and corporate staff have access to filtered supplies and private healthcare (Babatunde, 2020; Olalekan et al., 2019). This spatial and socio-economic divide underscores the racialised and class-based dynamics of ecological harm, where the burdens of pollution fall disproportionately on poor, indigenous populations who lack political voice or legal recourse.

Despite Nigeria’s constitutional commitment to environmental protection (Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, Section 20) and its ratification of international instruments like the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR, Article 24), the enforcement remains alarmingly weak. Regulatory bodies like the NOSDRA are often underfunded, undermined by political interference or outright captured by the same corporations they are meant to oversee (Okeke, 2025; Olawuyi, 2023). This regulatory failure emboldens polluters and entrenches a culture of impunity, where lives are routinely sacrificed for profit.

Furthermore, compensation for affected communities is often inadequate, delayed or entirely absent. Victims of oil pollution face significant legal barriers, including the burden of proof, slow judicial processes and intimidation, making it nearly impossible to hold polluters accountable (Amnesty International & Centre for Environment, Human Rights and Development (CEHRD), 2012; United Nations Environment Programme, 2011). This systemic judicial marginalisation compounds the material dispossession already suffered by these communities, trapping them in cycles of poverty and illness.

Thus, the water crisis in the Niger Delta is not merely the result of technical or environmental mismanagement; it is the predictable consequence of a political economy built on extractive capitalism, regulatory neglect and environmental injustice. Addressing it requires more than technical fixes or token corporate social responsibility. It demands systemic transformation rooted in justice, accountability and the democratisation of environmental governance.

A Policy-oriented Critique of State Complicity

One of the most damning dimensions of Nigeria’s environmental crisis in the Niger Delta is the complicity, or at the very least, wilful negligence of state institutions in perpetuating ecological injustice. Far from acting as a neutral arbiter or protector of public goods, the Nigerian state has repeatedly failed to uphold its constitutional responsibility to safeguard the environment and ensure equitable access to clean water and natural resources. This failure is not merely one of limited capacity or insufficient resources; it is deeply rooted in a predatory political economy shaped by corruption and a governance architecture that privileges extractive capital over environmental justice and human welfare.

A poignant example of this complicity is the long-delayed and poorly executed Ogoniland Cleanup Project. Following a groundbreaking 2011 report by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), which exposed extreme levels of hydrocarbon pollution in Ogoni communities, the Nigerian government committed to a multi-billion-dollar remediation effort through the HYPREP (United Nations Environment Programme, 2011). However, more than a decade later, progress remains minimal and largely symbolic.

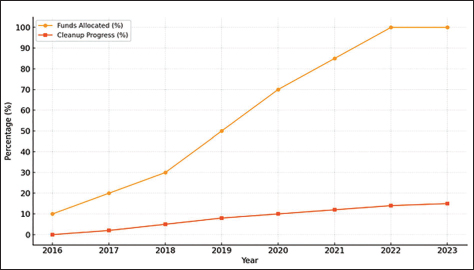

As depicted in Figure 3, while over 85% of the pledged financial resources had been allocated by 2022, less than 15% of the actual remediation had been implemented. This disjuncture between financial commitments and physical outcomes suggests not only bureaucratic inefficiency but also elite capture, fiscal opacity and systemic institutional decay. Investigations by civil society organisations and international watchdogs have revealed patterns of misappropriation, inflated contracts, opaque procurement practices and the appointment of politically connected yet technically unqualified personnel to key positions within HYPREP (Amnesty International, 2022; United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative, 2021).

Moreover, affected communities continue to report exclusion from decision-making processes, thereby reproducing colonial and postcolonial patterns of top-down governance that treat local populations not as stakeholders but as passive beneficiaries of state largesse.

Figure 3. Ogoniland Clean-up Progress (2016–2023) Versus Funds Allocated.

Source: Amnesty International (2022).

Further compounding the issue is the Nigerian state’s consistent failure to enforce environmental regulations and penalise corporate violators, especially multinational oil corporations. Despite repeated implications of companies such as Shell in oil spills and ecological destruction, enforcement actions remain rare, while legal proceedings are often protracted, opaque or inconclusive (Amnesty International, 2022; United Nations Environment Programme, 2011). This regulatory laxity is not accidental; it is symptomatic of a ‘petro-state’ logic, where fiscal dependency on oil revenue blunts political will to hold corporations accountable (Ibaba, 2008; Spanish Institute for Strategic Studies, 2017). In such a context, the state becomes both regulator and beneficiary of extractivism, an inherent conflict of interest that undermines the integrity and credibility of any remediation agenda.

The broader implication is that state complicity, whether through active collusion or passive neglect, plays a critical role in sustaining water insecurity and environmental degradation in the Niger Delta. Without a radical shift in governance priorities from short-term revenue maximisation to long-term human and ecological security efforts at sustainable development will remain superficial and rhetorical. As scholars of political ecology have long argued, environmental harm is never merely a technical failure; it is a manifestation of entrenched power asymmetries, institutional biases and sociopolitical exclusion (Elijah, 2022; Ezinna et al., 2024).

Thus, addressing water sustainability in the Niger Delta demands more than infrastructural upgrades or donor-funded interventions. It requires deep structural reforms that dismantle the impunity of polluters, increase transparency in environmental governance and expand mechanisms of democratic accountability. This includes ensuring genuine community participation in environmental remediation, creating independent oversight bodies and strengthening access to justice for victims of environmental harm.

Community Resistance and Alternative Governance Models: Lessons from the Global South

The Niger Delta is not just a site of environmental degradation and governmental failure, it is also a dynamic terrain of grassroots resistance and experimental governance alternatives. In response to the ecological destruction wrought by extractive industries and the complicity of the Nigerian state, local communities have emerged as powerful agents of environmental defence and water sustainability. These community-led interventions, often operating under conditions of extreme political and economic marginalisation, offer innovative and situated models of resistance and governance that challenge dominant paradigms and call for a fundamental reconfiguration of state–society–nature relations.

From the watershed struggle of the Ogoni people under the leadership of Ken Saro-Wiwa to more contemporary grassroots movements across Bayelsa, Delta and Rivers States, community resistance in the Niger Delta has been long-standing, multifaceted and strategically adaptive (Bamidele, 2016, 2017; Yakubu, 2017). These movements go beyond episodic protests; they constitute a sustained counter-narrative to developmentalism and oil dependency, articulating a political vision rooted in environmental justice, collective rights and sustainable livelihoods.

A key manifestation of this local agency is the development of community-based environmental monitoring systems. In several riverine communities, youth groups and women’s associations have initiated informal water-testing regimes using low-cost kits to track hydrocarbon pollution, acidity levels and waterborne pathogens (Sheriff et al., 2025). The data generated are then used to guide communal decision-making and to hold corporations and public authorities accountable. For instance, in Gbaramatu and Erema communities, citizen science has been instrumental in documenting oil spills and pipeline leaks that both the state and corporations have attempted to suppress or ignore (Bamidele, 2016; Manetu & Karanja, 2021; United Nations Environment Programme, 2011). These initiatives represent a form of emergent environmental citizenship that reclaims both epistemic authority and political agency from technocratic and exclusionary institutions.

Importantly, these forms of grassroots environmentalism are not unique to Nigeria. Similar dynamics are observable in other oil-producing regions of the Global South, particularly in the Amazonian zones of Ecuador and the Orinoco Belt of Venezuela, where Indigenous and local communities have mobilised against extractivist encroachment with remarkable resilience and creativity. In Ecuador, for example, Indigenous organisations such as CONAIE and Amazon Watch have spearheaded transnational legal campaigns against Chevron (formerly Texaco) for massive oil contamination in the Lago Agrio region. While the lawsuit has faced significant setbacks, it has nonetheless set a global precedent for corporate accountability and demonstrated the capacity of grassroots actors to engage at transnational legal and discursive levels (Dismantle Corporate Power, 2019; Sarliève, 2019).

Similarly, in Venezuela, despite an increasingly authoritarian political environment, Indigenous communities in the Orinoco region have enacted forms of ecological resistance, including road blockades, alternative land titling schemes and cultural revitalisation initiatives as strategies to resist oil expansion and safeguard water sources essential to their survival (Bello, 2020; Salas Rodriguez, 2025). These experiences resonate with the Niger Delta, not only in the shared ecological and political violence of extractivism but also in their reliance on local cosmologies, moral economies and traditional ecological knowledge to envision alternative futures.

What unites these movements across Nigeria, Ecuador and Venezuela is a fundamental critique of ‘resource sovereignty’ as currently practised, a sovereignty that concentrates control of natural wealth in the hands of state elites and multinational firms, often to the exclusion and detriment of local populations. Instead, these movements advocate for ‘resource democracy’: the right of communities to determine the terms under which resources are extracted (if at all) and to share equitably in the benefits. This shift from technocratic and top-down governance to participatory, place-based governance has profound implications for water sustainability. It reframes communities not as mere stakeholders, but as rightsholders and stewards of their ecosystems (Shunglu et al., 2022).

Nevertheless, significant challenges remain. In Nigeria, as in other extractivist states, the militarisation of oil zones, the co-optation of local leaders and the criminalisation of protest continue to undermine grassroots resistance. In many cases, state actors have deliberately fragmented community efforts by sponsoring parallel associations or exploiting ethnic and communal divisions. Moreover, the absence of formal institutional frameworks to recognise and support community-based environmental governance renders many of these initiatives precarious, underfunded and overly reliant on non-governmental organisations (NGOs) for visibility and technical support (Isukuru et al., 2024; Ojaduvba, 2025).

Yet, in spite of these structural constraints, these movements exemplify what Chatterjee (2004) terms ‘political society’ groups that, though denied full recognition by the state, nevertheless assert political claims through alternative and informal practices. In doing so, they expand the frontiers of environmental democracy and provide valuable insights for rethinking sustainability beyond market-based logics and technocratic fixes.

Therefore, recognising and integrating these grassroots governance models into national and international policy frameworks is imperative. Water sustainability in oil-producing regions cannot be achieved through top-down regulation alone. It requires a radical redistribution of power, recognition of situated ecological knowledge and the institutionalisation of bottom-up governance systems that are both contextually grounded and democratically accountable.

Community Resistance and Environmental Justice Movements

The protracted environmental degradation and water contamination in the Niger Delta have catalysed profound resistance from local communities, reflecting a dynamic interplay between environmental harm and sociopolitical contestation. Far from passive victims, Niger Delta communities have emerged as key actors in an environmental justice movement that challenges the hegemonic extractive paradigm imposed by both the Nigerian state and transnational oil corporations (Bamidele, 2016, 2017). This resistance underscores a critical argument: sustainable water governance cannot be achieved without acknowledging the political agency of affected populations and addressing the structural injustices embedded in resource extraction.

As illustrated in Figure 4, key hotspots for resistance activities are clustered around major oil-producing areas such as Ogoniland, Bayelsa and Rivers State. These regions have witnessed persistent demonstrations, sit-ins and legal advocacy directed at both oil companies and state institutions. The map emphasises not only the intensity but also the geographic diffusion of grassroots mobilisation, underscoring the widespread character of community activism despite systemic repression and limited institutional support.

Historically, movements such as the Ogoni struggle epitomise this contestation, offering a potent critique of how extractive industries externalise environmental costs onto marginalised populations while retaining profits (Bamidele & Erameh, 2023; Yakubu, 2017). The Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP), through strategic mobilisation and international outreach, exposed the entrenched nexus of corporate impunity, state complicity and environmental racism (Bamidele, 2016; Bamidele & Erameh, 2023). By framing environmental degradation as a violation of human rights and demanding systemic redress, MOSOP not only disrupted dominant narratives but also positioned water and land as inalienable communal rights rather than commodified assets (Bamidele, 2016; Barry, 2010). The enduring legacy of this movement reinforces the broader argument that environmental justice is inseparable from struggles for political autonomy and equitable development.

Figure 4. Map of Protest Hotspots and Community Resistance in the Niger Delta.

Contemporary civil society organisations have extended this legacy by amplifying community voices, documenting ecological abuses and pursuing legal actions to hold polluters accountable. Institutions such as the UNEP have played an instrumental role in translating local grievances into actionable policy demands, especially concerning the implementation of UNEP’s 2011 report on Ogoniland. However, this activism also highlights a critical gap: despite the presence of regulatory frameworks and international oversight, enforcement remains weak due to entrenched corruption, bureaucratic inertia and political interference (Mulade et al., 2025; United Nations Environment Programme, 2011). The gap between policy formulation and implementation reflects a systemic governance failure to prioritise water sustainability and community well-being over extractive economic interests.

Local communities have responded with remarkable resilience by employing diverse strategies of resistance ranging from non-violent protest and awareness campaigns to grassroots environmental monitoring. Particularly notable is the leadership of women’s associations, who foreground the intersection of gender and environmental justice by defending water sources vital for domestic and agricultural survival (Bamidele & Erameh, 2023; Odubo & Odubo, 2024). These initiatives emphasise a key theoretical insight: environmental justice struggles in the Niger Delta are deeply embedded in everyday life and relational networks, not merely abstract policy discourses. Yet the militarised repression of activists reveals the peril of such resistance, as oil firms frequently collaborate with state security forces to suppress dissent, thereby reproducing cycles of environmental violence and social exclusion.

However, while community resistance has secured partial and symbolic victories, its ability to effect systemic transformation remains curtailed by several structural constraints. Elite co-optation of protest leaders dilutes grassroots agendas, while ethnic and political fragmentation within the Delta impedes unified mobilisation. Furthermore, state institutions consistently prioritise oil revenue generation over environmental governance, leading to selective law enforcement and the neglect of impacted communities (Obiam & Amadi, 2022). These dynamics expose a broader political economy problem: the Nigerian state’s entanglement with extractivism obstructs meaningful reform and renders water pollution a normalised externality of ‘development’ (Bamidele & Erameh, 2023). Consequently, resistance must be situated within larger critiques of neoliberal and postcolonial developmentalism that entrench environmental dispossession.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the normative and epistemic significance of community resistance extends beyond immediate policy gains. By reframing water pollution as a matter of social and environmental justice rather than a purely technical or economic issue, these movements disrupt dominant paradigms that subordinate ecological and human rights to profit imperatives. This reframing aligns with SDG 6, which emphasises equitable access to clean water and the inclusion of marginalised voices in governance. In this light, community assertions of water rights constitute radical political acts that reimagine sustainability as participatory, rights-based and place-specific.

More broadly, such movements call for the institutionalisation of ecological democracy, a governance model rooted in transparency, participation and local stewardship (Shunglu et al., 2022).

This would require not just decentralisation of environmental decision-making but a fundamental reconfiguration of power between local communities, the state and multinational firms. Genuine participatory governance, strengthened accountability mechanisms and legal recognition of customary ecological knowledge systems are crucial to achieving this goal.

Community resistance in the Niger Delta thus represents both a vital challenge to entrenched environmental injustice and a hopeful foundation for transformative sustainability. The struggles of local populations illuminate the interconnectedness of ecological, political and social dimensions of water governance. Policy reforms grounded in environmental justice, not technocratic fixes, are indispensable for securing long-term water sustainability and upholding the dignity and well-being of Niger Delta communities for generations to come.

Policy Recommendations for Water Sustainability and Environmental Justice in the Niger Delta

Policy failure lies at the heart of the water crisis in Nigeria’s Niger Delta. Despite decades of environmental devastation caused by oil extraction, the Nigerian state has consistently prioritised extractive revenue over ecological integrity and human well-being. This failure stems not from the absence of environmental regulations, but from a persistent culture of weak enforcement, elite capture and institutional complicity. Effective policy reform must begin with an honest reckoning with these structural impediments. Without political will and institutional independence, environmental laws will remain symbolic gestures rather than instruments of justice and sustainability.

The Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) framework, though legally mandated, has often become a procedural formality that rubber-stamps extractive projects. Reforms must transform EIAs from technocratic exercises into participatory processes, where affected communities hold legal power to approve, monitor or halt environmentally hazardous operations. Mandatory public disclosure of environmental data, particularly on water contamination and oil spills, should be institutionalised. Real-time, open-access digital platforms should be developed to facilitate independent monitoring by civil society, researchers and journalists.

At the core of Nigeria’s environmental impasse is the unchecked influence of multinational oil corporations, shielded by opaque partnerships and political patronage. This corporate impunity has delayed or derailed crucial remediation efforts, such as the slow and piecemeal implementation of UNEP’s cleanup recommendations for Ogoniland. To counter this, an independent Environmental Justice Commission should be established, with legal authority, multi-stakeholder oversight and strong community representation. Such a body could serve as both watchdog and redress mechanism, grounded in legitimacy and transparency.

Grassroots participation in environmental governance remains marginal, despite communities being the frontline victims of water contamination. Existing policies often frame them as passive recipients of aid. Local environmental monitoring networks, currently underfunded and institutionally neglected, should be integrated into Nigeria’s formal environmental governance structure. Legal reforms, earmarked funding and technical training are required to institutionalise community participation in water governance, making interventions more locally appropriate, sustainable and democratic.

The credibility of state-led interventions is further eroded by systemic corruption within development institutions, notably the NDDC. Billions of naira allocated for water infrastructure, remediation and community restoration have been mismanaged or siphoned off. Comprehensive institutional reform must include anti-corruption safeguards, transparent procurement processes, independent audits and strong penalties for diversion of public funds. Furthermore, community representation on oversight and procurement boards can enhance transparency and ensure developmental priorities reflect urgent, lived needs, particularly regarding clean water access and pollution control.

Beyond national reforms, international legal instruments and accountability mechanisms offer critical leverage. Given the transnational operations of oil corporations, those headquartered in the Global North should be held legally accountable for environmental harms in their host communities. Recent court victories by Niger Delta plaintiffs in foreign jurisdictions confirm the viability of extraterritorial litigation as a path to justice. In addition, climate finance mechanisms, including those aligned with the ‘loss and damage’ framework, should prioritise the Niger Delta as a climate sacrifice zone, channelling resources to locally driven water infrastructure and ecosystem restoration efforts.

A truly sustainable water future for the Niger Delta requires a shift from technocratic policy fixes to a justice-oriented ecological paradigm. Environmental degradation here is not simply an ecological concern, but a profound manifestation of social and spatial injustice. Policy must therefore be reimagined as a vehicle for equity, dignity and ecological survival, grounded in Nigeria’s constitutional and international human rights obligations, particularly the rights to water, health, life and a clean environment. Aligning Nigeria’s environmental policy with SDGs 6 (clean water and sanitation) and 16 (peace, justice and strong institutions) would institutionalise environmental justice as a foundational national priority.

Only through such a multi-scalar, participatory and justice-driven approach can the Niger Delta move from ecological crisis to sustainable renewal. Water sustainability must not be treated as a technical challenge, but as a political imperative demanding structural reform, democratic accountability and reparative action.

Concluding Reflections and Thematic Synthesis

The crisis of water sustainability in Nigeria’s Niger Delta is emblematic of the contradictions inherent in resource-dependent and extractivist economies. Environmental degradation, particularly the persistent pollution of water sources, is not a collateral outcome of development but a structural and systemic feature of oil extraction. This study has examined how the entanglement of extractive capitalism, state complicity and corporate irresponsibility has transformed water from a public good into a site of dispossession, resistance and ecological injustice. The Niger Delta today stands not only as an environmental disaster zone but as a political terrain where struggles over access, accountability and survival converges.

A central theme emerging from this analysis is the entrenched logic of extractivism that informs both state policy and corporate practice. Oil operations in the region have consistently externalised environmental costs onto marginalised populations. Oil spills, gas flaring and hazardous waste disposal are not isolated incidents; they are normalised through a regime of regulatory inertia and institutional capture. This constitutes a form of environmental authoritarianism, wherein the state’s silence and inaction serve as mechanisms of rule that enable pollution and shield violators from consequences.

Crucially, this ecological crisis must be situated within the broader political economy of marginalisation. Communities in the Niger Delta bear the greatest burden of environmental harm, yet remain systematically excluded from environmental governance. Their indigenous knowledge systems and stewardship practices are consistently overlooked by state and corporate actors. However, these communities are not simply victims. Through litigation, protest and grassroots innovation, they have developed robust strategies of resistance, challenging the dominance of extractive interests and asserting their right to water and a healthy environment.

The shortcomings of high-profile remediation efforts, such as the Ogoniland cleanup, further illuminate the gap between policy rhetoric and operational reality. Despite substantial funding, progress remains halting, opaque and riddled with allegations of corruption and elite manipulation. The failure of these initiatives reveals not just logistical deficiencies but a crisis of institutional legitimacy. Genuine reform must thus go beyond technical interventions to confront structural governance failures demanding transparency, anti-corruption safeguards and inclusive decision-making frameworks.

This study demonstrates that water insecurity in the Niger Delta is not merely an ecological issue; it is a form of structural violence, produced by policy choices that systematically prioritise profit over people. Governance architectures that allow environmental harm to persist represent a betrayal of constitutional and human rights obligations. In this context, the pursuit of water sustainability must be rooted in a justice-oriented framework, one that addresses underlying power asymmetries, restores community agency and reimagines development in service of ecological and social well-being.

SDG 6, which advocates for universal access to clean water and sanitation, provides a normative benchmark for this transformation. Realising SDG 6 in the Niger Delta requires not just policy alignment but a deep restructuring of environmental governance, full and transparent implementation of remediation projects and the institutionalisation of community-led water governance models. Given the global dimensions of oil extraction, international accountability mechanisms and financial support are also essential. Climate justice frameworks, especially those focused on loss and damage, should prioritise the Niger Delta as a frontline sacrifice zone in need of reparative justice and ecological restoration.

Most importantly, the water crisis in the Niger Delta serves as a litmus test for Nigeria’s commitment to environmental justice and sustainable development. It reveals the deeper stakes of SDG 6, not merely as a development target, but as a critical measure of whose lives, territories and futures are deemed expendable in the pursuit of growth. Addressing this crisis is about more than ecological repair; it is about restoring equity, rights and dignity to some of Nigeria’s most disenfranchised populations and reasserting the primacy of life over profit.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Seun Bamidele  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9782-6543

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9782-6543

Achunike, O. (2020). Social impacts of oil extraction in the Niger Delta region, Nigeria [Master’s thesis, University of Northern British Columbia Institutional Repository].

Agbakoba, O. (2025, April 22). Oil pollution a national crisis requiring urgent intervention. The Nation. https://thenationonlineng.net/oil-pollution-a-national-crisis-requiring-urgent-intervention/

Akaakar, F. O. (2025). Challenges to the effective performance of environmental institutions in Nigeria: How far? So far? International Journal of Innovative Research & Development, 14(1), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.24940/ijird/2025/v14/i1/JAN25005

Al Jazeera. (2021, February 12). UK top court allows Nigerian farmers to sue Shell over oil spills. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/2/12/uk-supreme-court-gives-ok-to-sue-shell-over-oil-spills

Amnesty International. (2018). Negligence in the Niger Delta: Decoding Shell and Eni’s poor record on oil spills (Index: AFR 44/7970/2018). https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr44/7970/2018/en/

Amnesty International. (2022). Amnesty International report 2021/22: The state of the world’s human rights. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol10/4870/2022/en/

Amnesty International & Centre for Environment, Human Rights and Development (CEHRD)., Development (2012). Another Bodo oil spill, another flawed oil spill investigation in the Niger Delta (Index: AFR 44/037/2012). https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/afr44/037/2012/en/

Ansari, S. (2024, October 14). The economic paradox of Nigeria: Oil wealth and underdevelopment. Economics Online. https://www.economicsonline.co.uk/managing_the_economy/the-economic-paradox-of-nigeria-oil-wealth-and-underdevelopment.html

Babatunde, A. O. (2020). Oil pollution and water conflicts in the riverine communities in Nigeria’s Niger Delta region: Challenges for and elements of problem-solving strategies. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 38(1), 1–20.

Bamidele, O. (2016). Resurgence of militancy in Ogoniland: Socio-economic perspective. Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy and International Relations, 5(9), 165–188. https://doi.org/10.22456/2238-6912.66562

Bamidele, S. (2017). The resurgence of the Niger-Delta Avengers (NDAs) group in the Niger-Delta region of Nigeria: Where does the economic deprivation lie? International Journal of Group and Minority Rights, 24(4), 537–552.

Bamidele, S., & Erameh, I. N. (2023). Environmental degradation and sustainable peace dialogue in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. Resources Policy, 80, 103274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.103274

Barry, F. B. (2010 May 5). Environmental injustices: Conflict health hazards in the Niger Delta (Substantial research paper). American University, School of International Service.

Bello, M. A. (2020, December 16). Venezuela: Mining impacts on Indigenous communities. Youth4Nature. https://www.youth4nature.org/blog/venezuela-indigenous-communities

Bello, A., & Nwaeke, T. (2023). Impacts of oil exploration (oil and gas conflicts; Niger Delta as a case study). Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 11, 189–200. https://doi.org/10.4236/gep.2023.113013

Brisibe, B. V. (2024). Exploring the legal challenges to corporate environmental responsibility regulation in Nigeria’s petroleum industry. African Journal of Law and Human Rights, 8(2), 47–56.

Chatterjee, P. (2004). The politics of the governed. Columbia University Press.

Dismantle Corporate Power. (2019, April 4). The case of Chevron in the Ecuadorian Amazon: The ruling of the Supreme Court of Canada closes the doors to end impunity. Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/the-case-of-chevron-in-the-ecuadorian-amazon-the-ruling-of-the-supreme-court-of-canada-closes-the-doors-to-end-impunity/

Elijah, A. A. (2022). A review of the environmental impact of gas flaring on the physiochemical properties of water, soil and air quality in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Earthline Journal of Chemical Sciences, 7(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.34198/ejcs.7122.3552

Eweje, G. (2006). Environmental costs and responsibilities resulting from oil exploitation in developing countries: The case of the Niger Delta of Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 69(1), 27–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9067-8

Ewim, D. R. E., Orikpete, O. F., Scott, T. O., Onyebuchi, C. N., Onukogu, A. O., Uzougbo, C. G., & Onunka, C. (2023). Survey of wastewater issues due to oil spills and pollution in the Niger Delta area of Nigeria: A secondary data analysis. Bulletin of the National Research Centre, 47, 116. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-023-01090-1

Ezinna, P. C., Ugwuibe, C. O., & Okwueze, F. O. (2024). Gas flaring, sustainable development goal 2 and food security reflections in the Niger Delta area of Nigeria. Discover Global Society, 2, 61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-024-00075-3

Gbadamosi, F., & Aldstadt, J. (2025). The interplay of oil exploitation, environmental degradation and health in the Niger Delta: A scoping review. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 30(5), 351–367.

Ghazvinian, J. (n.d.). Untapped: The scramble for Africa’s oil. Harcourt Inc.

Hart, A. O. (2024). Oil exploration, water quality and public health in Bonny and other Niger Delta communities. Sunrise Publishers.

Ibaba, S. I. (Ed.). (2008). The Nigerian state, oil industry and the Niger Delta. Proceedings of the first international conference of the Department of Political Science, Niger Delta University, Wilberforce Island, Bayelsa State, in collaboration with the Center for Applied Environmental Research, University of Missouri, Kansas City, USA, March 11–13, 2008. Niger Delta University.

Isukuru, E. J., Opha, J. O., Isaiah, O. W., Orovwighose, B., & Emmanuel, S. S. (2024). Nigeria’s water crisis: Abundant water, polluted reality. Cleaner Water, 2, 100026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clwat.2024.100026

Kodiya, M. A., Modu, M. A., Ishaq, K., Yusuf, Z., Wakili, A. Z., Dayyabu, N., Jibrin, M. A., & Babangida, M. U. (2025). Environmental pollution in Nigeria: Unlocking integrated strategies for environmental sustainability. African Journal of Environmental Sciences and Renewable Energy, 18(1), 30–50.

Leigh Day. (2021, February 12). UK: Supreme Court rules that polluted Nigerian communities can sue Royal Dutch Shell in the English courts. Business & Human Rights Resource Centre. https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/uk-supreme-court-rules-that-polluted-nigerian-communities-can-sue-royal-dutch-shell-in-the-english-courts/

Manetu, W. M., & Karanja, A. M. (2021). Waterborne disease risk factors and intervention practices: A review. Open Access Library Journal, 8, 1–11. https://www.scirp.org/journal/oalibj/

Mbalisi, C. N., & Nwaiwu, N. S. (2025). United in violent relations: Water resources, environmental pollution, and conflict in South-South Nigeria since 1999. Ohazurume: UNIZIK Journal of Culture and Civilization, 4(2), 191–212.

Mbao, M. L., & Osinibi, O. M. (2014). Confronting the problems of colonialism, ethnicity and the Nigerian legal system: The need for a paradigm shift. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(27), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p168

Mulade, S., Clark, E. V., & Ikenga, F. A. (2025). Oil spillage in the Niger Delta: Government and oil companies remediation activities. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 6(5), 7436–7442. https://www.ijrpr.com

Ndinwa, C. C. G., & Akpafun, S. (2012). Environmental impacts of oil exploration and exploitation in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria. Journal of Environmental Management and Safety, 3(1), 159–183.

Nriagu, J. (2011). Oil industry and the health of communities in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. In Nriagu J. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of environmental health. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-52272-6.00736-4

Obiam, S. C., & Amadi, O. S. (2022). The Nigerian state and development in the Niger Delta region. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews, 14(1), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2022.14.1.0296

Odubo, T. R., & Odubo, T. V. (2024). Environmental impact of oil pollution on income and livelihood sustainability in rural communities of the Niger Delta region, Nigeria. Ghana Journal of Geography, 16(4), 15–23.

Ogbu, A. D., Ozowe, W., & Ikevuje, A. H. (2024). Oil spill response strategies: A comparative conceptual study between the USA and Nigeria. GSC Advanced Research and Reviews, 20(1), 208–227. https://doi.org/10.30574/gscarr.2024.20.1.0262

Oishy, M. N., Shemonty, N. A., Fatema, S. I., Mahbub, S., Mim, E. L., Raisa, M. B. H., & Anik, A. H. (2025). Unravelling the effects of climate change on the soil-plant-atmosphere interactions: A critical review. Soil & Environmental Health, 3(1), 100130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seh.2025.100130

Ojaduvba, A. O. J. (2025). Corruption and financial mismanagement in the Niger Delta Development Commission. International Journal of Innovative Legal & Political Studies, 13(2), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15192297

Okeke, C. (2025, January 10). Environmental rights as constitutional rights: Nigeria’s legal evolution. OAL Publication. https://oal.law/environmental-rights-as-constitutional-rights-nigerias-legal-evolution/

Olalekan, R. M., Omidiji, A. O., Adedipe, A. A., Babatunde, A., Odipe, O. E., & Sanchez, N. D. (2019). “Digging deeper”: Evidence on water crisis and its solution in Nigeria for Bayelsa State: A study of current scenario. International Journal of Hydrology, 3(4), 244–257. https://doi.org/10.15406/ijh.2019.03.00187

Olawuyi, M. T. (2023). Corporate accountability for climate change and natural environment in Nigeria: Trends, limitations and future directions. The Journal of Sustainable Development Law and Policy, 15(1), 286–323. https://doi.org/10.4314/jsdlp.v15i1.10

Omokaro, G. O. (2024). Oil extraction and the environment in Nigeria’s Niger Delta: A political-industrial ecology (PIE) perspective. Asian Journal of Advanced Research and Reports, 18(11), 161–169. 10.9734/ajarr/2024/v18i11784

Salas Rodriguez, L. (2025, February 1). Gold or life: The struggle of Venezuelan Indigenous Peoples against illegal mining. Debates Indígenas. https://debatesindigenas.org/en/2025/02/01/gold-or-life-the-struggle-of-venezuelan-indigenous-peoples-against-illegal-mining/

Sarliève, M. (2019, March 14). Ecuador: Toxic justice and tourism by Texaco waste pools. Justice Info. https://www.justiceinfo.net/en/40565-ecuador-toxic-justice-and-tourism-by-texaco-waste-pools.html

Sheriff, M., Clark, E. V., & Ikenga, F. A. (2025). Oil spillage in the Niger Delta: Government and oil companies remediation activities. International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, 6(5), 7436–7442. https://www.ijrpr.com

Shunglu, R., Köpke, S., Kanoi, L., Nissanka, T. S., Withanachchi, C. R., Gamage, D. U., Dissanayake, H. R., Kibaroglu, A., Ünver, O., & Withanachchi, S. S. (2022). Barriers in participative water governance: A critical analysis of community development approaches. Water, 14(5), 762. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14050762

Secretaría General Técnica. (2017). Spanish official publications catalogue (Print on demand: NIPO 083-16-308-8; e-book: NIPO 083-16-309-3). Spanish Ministry of Defense.

Ukhurebor, K. E., Athar, H., Adetunji, C. O., Aigbe, U. O., Onyancha, R. B., & Abifarin, O. (2021). Environmental implications of petroleum spillages in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria: A review. Journal of Environmental Management, 293, 112872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112872

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2015). Goal 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. Sustainable Development Goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal6

United Nations Environment Programme. (2011). Environmental assessment of Ogoniland. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/7947

United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI). (2021). UNEP FI annual overview 2021. https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/UNEP-FI-2021-Annual-Overview.pdf

Wami-Amadi, C. (2025). The impact of air borne toxins from gas flaring on cardiopulmonary and other systemic functions. Scholars International Journal of Anatomy and Physiology, 8(1), 12–28. https://doi.org/10.36348/sijap.2025.v08i01.003

Yakubu, O. H. (2017). Addressing environmental health problems in Ogoniland through implementation of United Nations Environment Program recommendations: Environmental management strategies. Environments, 4(2), 28. https://doi.org/10.3390/environments4020028