1Faculty of Management Studies and Research, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

In the present business scenario, organisations grapple with continuous disruption driven by competition, technological advancements, geopolitical volatility and an increasingly informed consumer base. This evolving environment has shifted from the VUCA model (volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity) to the BANI framework (brittle, anxious, nonlinear and incomprehensible). To navigate these challenges, resilience and agility have become crucial for organisations, necessitating the development of a supportive culture and competent workforce. Amidst newspaper reports of toxic leadership and toxic culture prevailing in Indian banking sector, employee wellbeing has become a significant aspect for better performance in recent times. As India aims to become $5 trillion economy by FY 2025–26, the Indian banking sector is expected to align itself with this objective and perform efficiently. In this backdrop, it can be argued that spiritual leadership may act as toxin handler and influence job engagement through spiritual wellbeing. This research study aims to explore the relationship between spiritual leadership, spiritual wellbeing and job engagement in the Indian banking sector. The proposed conceptual framework, derived from Fry’s (2005) Causal Model of Spiritual Leadership, indicates ‘vision’, ‘hope/faith’ and ‘altruistic love’ as components of spiritual leadership and ‘meaning/calling’ and ‘membership’ as components of spiritual wellbeing. The conceptual model is then tested using partial least squares structural equation modelling and the result confirms that spiritual wellbeing is a significant predictor of ‘job engagement’ in the Indian banking sector. Further, this study establishes the critical role of spiritual leadership in enhancing overall employee wellbeing. Leadership is a crucial factor in creating the right work environment and practicing spiritual leadership would help nurture an engaged workforce.

Spiritual leadership, spiritual wellbeing, job engagement, employee wellbeing, workplace spirituality

Introduction

As India aims to become $5 trillion economy by FY 2025–26, the Indian banking sector is expected to align itself with this objective and perform efficiently. According to the newspaper reports, in FY 2023–24 so far, the bank credit has been growing at the rate of 15% per annum. The overall non-performing assets also decreased. However, raising retail deposits remained a challenge in this highly competitive sector. As a consequence, the bank employees are under much pressure to perform consistently. In recent times, several incidents of verbal and other forms of abuse of senior employees to their subordinates generated wide debate on the presence of ‘toxic leadership’ and ‘toxic work culture’ vis-à-vis employee wellbeing and sustainable practices in the Indian banking sector.

Research on toxic work culture is more of a recent phenomenon. Frost (2003) was one of the early researchers on this topic who proposed that workplace toxicity originates due to ignorance of emotions that people contain about their workplace. A toxic workplace negatively impacts an employee’s confidence, self-esteem and self-worth. While the short-term effects of workplace toxicity are fatigue and irritability, the long-term effects could be clinical depression and heart disease. Frost further proposed the concept of ‘toxic handlers’—the compassionate and caring individuals who help their fellow colleagues to combat stress and thus contribute significantly to create a healthy organisation.

Other researchers such as Appelbaum and Roy-Girard (2007), George (2023) established the fact that toxic managers or leaders and toxic culture largely result in destructive and ineffective toxic organisations. Anjum and Ming (2018) and Rasool (2021) observed that workplace harassment, workplace bullying and workplace ostracism act as detrimental factor towards employee motivation and engagement and productivity.

On the other hand, the desire for alternative leadership styles gained momentum since 2000s as several cases of fraudulent and dishonest acts, distrust, low employee engagement and employee turnover continued, and organisations tried to address such issues by adopting alternative leadership approaches such as spiritual leadership. Influence of workplace spirituality on employee wellbeing has been studied by several researchers in recent past (Khatri & Gupta, 2017; Pawar, 2016). Taking a cue from the existing literature, this study aims to establish a relationship between spiritual leadership, spiritual wellbeing (SWB) and job engagement in Indian banking sector, based on an empirical survey.

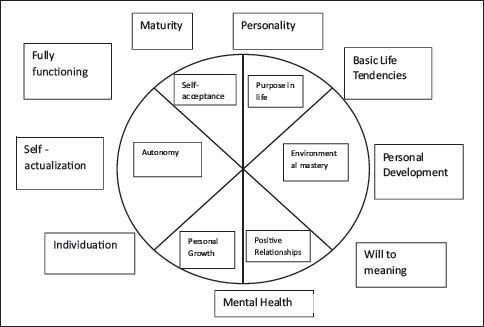

Figure 1. Core Dimensions of Psychological Wellbeing.

Source: Adapted from Ryff and Singer (2008).

Literature Review and Hypothesis Formation

Spiritual Wellbeing and Employee Wellbeing: The Interconnection

Moberg was one of the early researchers on the subject of SWB who explained SWB as ‘man’s inner resources, especially his ultimate concern, the basic value around which all other values are focused, the central philosophy of life that guides a person’s conduct’ (Moberg, 1984). He further explained the concept as having two components—vertical dimension or religious wellbeing and horizontal dimension or existential wellbeing. While religious wellbeing is more connected to supreme divinity or an eternal power, existential wellbeing is the sense of purpose in life, peace and life satisfaction (Su et al., 2009) or, one’s relationship with oneself, and with the environment. Moberg’s contemporary researcher Ellison suggested that SWB has been an outcome of spiritual health of an individual (Ellison, 1983). With time, the functional definition of SWB got more associated with ‘health’ in totality of the inner resources of people, a sense of within-person integration or connectedness. Dhar et al. (2013) stated that SWB is ‘one of the most important dimensions of human well-being’. On the other hand, Fisher (2011) proposed the Four Domains Model of SWB where the identified domains have been ‘personal’, ‘communal’, ‘environmental’ and ‘transcendental’. The ‘personal’ domain includes attributes such as meaning, purpose and values (self-awareness).

Ryff (1989, 2014, 2018), another prominent researcher in the field of psychological wellbeing (PWB), developed the scale of PWB consisting of six constructs, namely, ‘autonomy’, ‘environmental mastery’, ‘personal growth’, ‘purpose in life’, ‘positive relations with others’ and ‘self-acceptance’. The core dimensions of PWB are mentioned in Figure 1. On the other hand, a meaningful life or purpose in life is also a dimension of SWB. Park et al. (2017) mentioned that SWB comprises belief, meaning and peace.

The concept of wellbeing has wide range of explanations such as ‘an individual’s perception of life, happiness, meaning and purpose, work satisfaction, personal development, or social relationships’ (Su et al., 2014). Wellbeing is ‘a state of mind wherein individuals perceive on mental health, happiness and also quality of work experiences’. Many researchers argued that wellbeing encompasses social, spiritual, emotional and intellectual wellbeing (McCarthy et al., 2011). Paloutzian and Ellison (1982) reported the spiritual well-being scale consisting of two major aspects of SWB—including a religious sense and an existential sense.

Job Engagement: An Important Workplace Outcome

Workplace outcomes across organisations depend on employees’ willingness to engage in their own jobs to a great extent (Bakker et al., 2016). Employee job engagement is also found to be important for achieving efficiency and good performance at individual (Bayighomog & Arasli, 2022), team (Seppälä et al., 2020) and organisational level (Yang et al., 2019).

Spiritual Leadership, SWB and Job Engagement

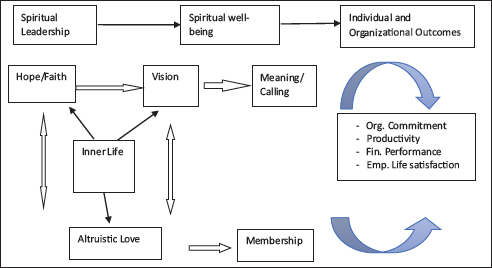

Fry et al. (2005) proposed causal model of spiritual leadership that involves intrinsically motivating and inspiring workers through ‘hope/faith’, ‘vision’ and ‘altruistic love’. Fry’s model proposes SWB as a higher-level construct with sub-dimensions of meaning/calling and membership. The purpose of spiritual leadership is to explore the basic needs of both the leader and followers for SWB and to fabricate vision and value agreement across the individual employee, teams and organisation as a whole.

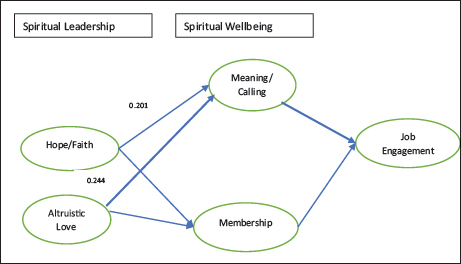

This study is focused on understanding spiritual leadership as a predictor of SWB as proposed by Fry’s Causal Model mentioned in Figure 2. Fry’s model describes spiritual leadership as a function of vision, hope/faith and altruistic love and SWB as function of meaning/calling and membership. Vision is explained as depiction of the future with some reason or explanation as to why that future needs to be attained. Hope/Faith is a desire with an expectation of fulfilment of vision. For spiritual leadership, Altruistic Love is defined as ‘a sense of wholeness, harmony, and wellbeing produced through care, concern, and appreciation for both self and others’. Further, Fry indicated two sub-dimensions of SWB, that is, a sense of meaning and membership. Meaning/Calling is the idea of questioning one’s existence which is the primary matter of human life. Work is one of the ways to find a sense of meaning in life. Meaning in work has also been studied in the empowerment model (Spreitzer et al., 1997) and the job characteristics model (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). Membership is a matter of interrelationships and connection through social interaction. People value their affiliations, being interconnected and the sense of belongingness to a larger community. Membership is often considered as the core of organisational culture (Fagley & Adler, 2012).

Figure 2. Causal Model of Spiritual Leadership proposed by Fry.

Source: Fry et al. (2005).

Some researchers indicated spiritual leadership as an important factor in the workplace that may impact subjective wellbeing. Further, it has been argued that spiritual leadership influences psychological ownership directly and through a mediating role of SWB (Arshad & Abbasi, 2014). Spiritual leadership is linked with various organisational outcomes, such as employee wellbeing and human health by means of SWB (Nielsen et al., 2009). SWB in turn influences employee morale, commitment, a sense of meaning and a job calling (Fry et al., 2005), greater employee and leader motivation, satisfaction and task involvement (Delbecq, 1999), and job engagement (Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008). This suggests that spiritual leadership–induced SWB has an impact on job engagement.

‘Job engagement’ refers to ‘the harnessing of organisation members’ selves to their work roles’ (Kahn, 1990). When an employee exercises high level of professional engagement, he or she will be more integrated into the role behaviour at work and at the same time would express himself or herself at work. In the process, the employee would become more engaged, satisfied and passionate about his or her work. There are two theoretical aspects of job engagement, one is ‘role theory’ and the other is resource ‘conservation theory’. The ‘role theory’ discusses why individuals have different degrees of engagement in their workplace. A high degree of engagement in the workplace is called ‘personal dedication’ to work, while a low degree of engagement is called ‘personal alienation’. Employees in their work ‘employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances’ (Kahn, 1990).

‘Resource conservation theory’ is first proposed by Hobfoll (1989) and is often used to explain the relationship between ‘job stress’ and ‘job burnout’ (Hunsaker, 2019). Job requirements are considered as the influencing factors of ‘threat of loss of precious resources’—the main cause of job burnout. On the contrary, job resources are considered as the influencing factors of the acquisition of additional precious resources that can reduce job burnout and even improve employees ‘job engagement’. Lack of work resources leads to individual alienation (Joormann, 2010; Schaufeli et al., 2006).

Csikszentmihalyi (2003) defines engaged employees as those who are immersed in their work and experience ‘a positive, fulfilling, work related state of mind that is characterised by vigour, dedication, and absorption’. On the other hand, employees with high levels of engagement usually score high on wellbeing aspect (Truss et al., 2013). Furthermore, Mendes and Stander (2011) argued that meaning, as one of the dimensions of SWB, is a predictor of work engagement.

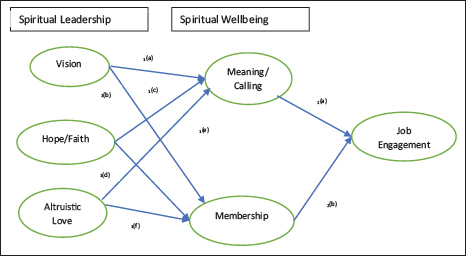

Building upon the above arguments, the present research hypothesises:

H1: Spiritual leadership is a predictor of SWB.

H1(a): Vision is a predictor of meaning/calling.

H1(b): Vision is a predictor of membership.

H1(c): Hope/Faith is a predictor of meaning/calling.

H1(d): Hope/Faith is a predictor of membership.

H1(e): Altruistic love is a predictor of meaning/calling.

H1(f): Altruistic love is a predictor of membership.

H2: SWB is a predictor of job engagement.

H2(a): Meaning/Calling is a predictor of job engagement.

H2(b): Membership is a predictor of job engagement.

Materials and Methods

Convenience sampling is adopted for the purpose while conforming to certain criteria such as representativeness. Convenience sampling is a ‘statistical method of drawing respondents by selecting people because of the ease of their volunteering or selecting units because of their availability or easy access’. Employees working in managerial level in the Indian banking sector (assistant manager and above) are approached for cross-sectional, questionnaire-based survey.

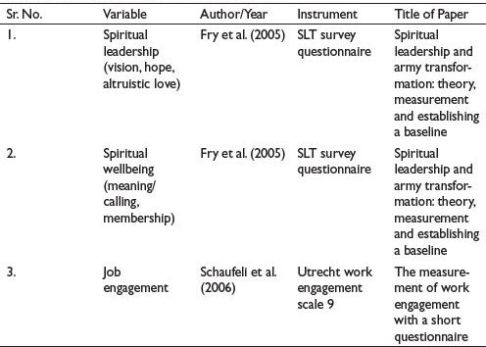

The questionnaire comprises statements for the constructs such as spiritual leadership, SWB and job engagement. To measure spiritual leadership and SWB, Fry’s SLT survey questionnaire is used (2005), whereas to measure job engagement, Schaufeli et al. (2006) Utrecht Work Engagement Scale 9 is used (refer to Table 1). The instrument uses nominal scales for placing data into categories such as age, years of experience and gender of the managers. Seven-point Likert-type scale is used to record the varying degree of agreement and disagreement with strongly disagree being 1 to strongly agree being 7, for a series of statements to capture their perception and interpretations.

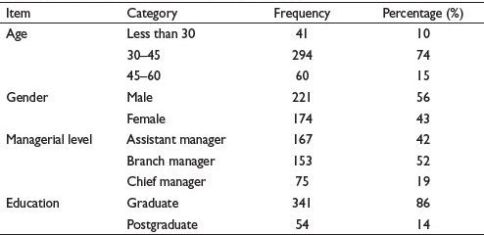

The pilot survey was performed on 50 samples, and reliability and internal consistency of the questionnaire were established by measuring Cronbach’s alpha and exploratory factor analysis. The survey instrument was then applied for more sample collection, and overall 395 responses were received (refer to Table 2). The questionnaire was distributed in the form of a Google form to the bank employees of both public and private sector banks. Age, gender, managerial level and education are control variables.

Table 1. Scales Adapted for the Present Research.

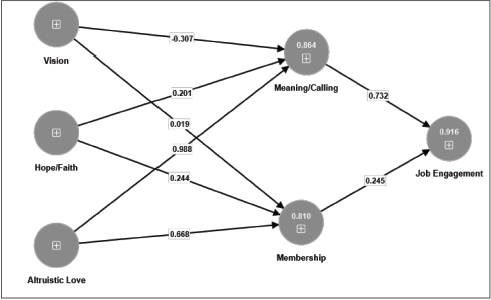

After data collection using the survey instrument, partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was applied to check relations between the constructs. Since PLS-SEM supports measuring complex models with a causal-predictive approach, the researchers felt that the causal nature of the conceptual model could be tested by using PLS-SEM technique Figure 3.

Proposed Conceptual Framework

Result

Assessment of Measurement Model

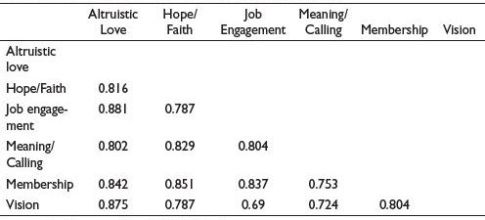

The measurement model is assessed by measuring factor/item loadings (for item’s contribution to its assigned construct), variance inflation factor (for co-linearity) Cronbach alpha (for reliability), composite reliability (CR, for assessing the reliability of the model) and average variance extracted (AVE, for convergent validity). The minimum acceptable limit for factor/item loadings, Cronbach’s alpha and CR is more than 0.7; for AVE, it is more than 0.5 and VIF is acceptable up to 10, and all the values mentioned in Table 3 are within the prescribed range. Discriminant validity is assessed by calculating the heterotrait–monotrait ration and found within permissible range of below 0.90 (Table 4).

Figure 3. Conceptual Model Proposed by the Researcher.

Table 2. Demographic Description of Sample Collected.

Assessment of Structural Model

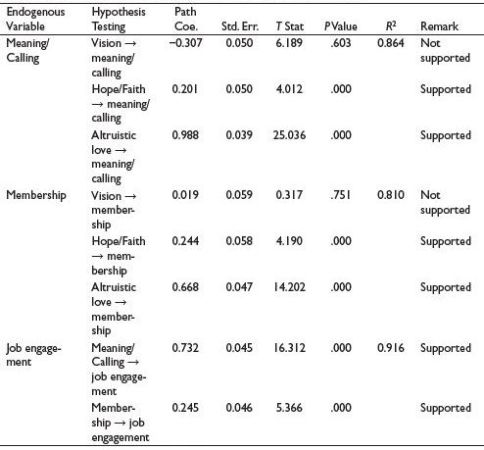

Once the measurement model is established, the structural model is assessed to evaluate proposed hypotheses as shown in Figure 4. The model presented a good fit with SRMR 0.076. Baring H1(b), all the hypotheses are significant as detailed in Table 5. Two-tailed, percentile bootstrap was performed at 0.05 significance level to test effects Figure 5.

Table 3. Assessment of Measurement Model.

Table 4. Discriminant Validity—Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio.

Source: Results received from PLS-SEM Analysis.

Figure 4. Assessment of Structural Model.

Table 5. Assessment of Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing.

Source: Results received from PLS-SEM Analysis.

Figure 5. Final Validated Structural Model.

Discussion

Out of three microvariables of spiritual leadership construct, that is ‘vision’, ‘hope/faith’ and ‘altruistic love’, ‘altruistic love’ emerged as significant predictor for ‘Meaning/Calling’ explaining variations (beta = 0.988) up to 98%. Another microvariable of spiritual leadership ‘hope/faith’ also influences ‘meaning/calling’, explaining variations (beta = 0.201) up to 20%. However, ‘vision’ emerged as no significant impact on ‘meaning/calling’. For ‘meaning/calling’, R2 value 0.864 denotes that the exogenous variables are substantially significant as the value is above 0.75 (Hair et al., 2013).

Further, out of three microvariables of spiritual leadership construct, that is ‘vision’, ‘hope/faith’ and ‘altruistic love’, ‘altruistic love’ and ‘hope/faith’ emerged as significant predictors for ‘membership’ explaining variations (beta = 0.668), up to 66%, and (beta = 0.244) up to 24%, respectively. ‘Vision’ emerged as having no significant impact on membership (beta = 0.019). For membership, R2 value 0.810 denotes that the exogenous variables are substantially significant as the value is above 0.75 (Hair et al., 2013).

Out of two microvariables of SWB, both ‘meaning/calling’ and ‘membership’ are significant predictors of ‘job engagement’, explaining variations (beta = 0.732), up to 73%, and (beta = 0.245) up to 24%, respectively. For job engagement, R2 value 0.916 denotes that both of the microvariables of SWB (‘meaning/calling’ and ‘membership’) are substantially significant as the value is above 0.75 (Hair et al., 2013).

Conclusion and Recommendation

Based on the results of hypothesis testing carried out in this study, it can be concluded that SWB has a positive effect on job engagement in employees of the Indian banking sector. In addition, it can also be concluded that the trait of altruistic love in the leader (managerial level employees in Indian banks) is a significant predictor of SWB. Moreover, the leader’s hope/faith in his vision also influences SWB.

Besides, this study also brings into notice an interesting fact that leader’s vision may exert a negative impact on meaning/calling. The present researchers recommend future studies in this regard to understand the reasons behind this.

Indian retail banks must focus on SWB as a part of overall wellbeing of its employees since it would benefit the organisation in terms of inculcating an engaged workforce. Future research studies may test this model to other sectors such as healthcare.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Ishani Chakraborty  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8694-0906

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-8694-0906

Anjum, A., & Ming, X. (2018). Combating toxic workplace environment: An empirical study in the context of Pakistan. Journal of Modelling in Management, 13(3), 675–697. https://doi.org/10.1108/JM2-02-2017-0023

Appelbaum, S. H., & Roy-Girard, D. (2007). Toxins in the workplace: Affect on organizations and employees. Corporate Governance, 7(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700710727087

Arshad, A., & Abbasi, A. (2014). Spiritual leadership and psychological ownership: Mediating role of spiritual wellbeing. Science International (Lahore), 26(3), 1265–1269.

Bakker, A. B., Rodríguez-Muñoz, A., & Sanz Vergel, A. I. (2016). Modelling job crafting behaviours: Implications for work engagement. Human Relations (New York), 69, 169–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726715581690

Bayighomog, S. W., & Arasli, H. (2022). Reviving employees’ essence of hospitality through spiritual wellbeing, spiritual leadership, and emotional intelligence. Tourism Management, 89, 104406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104406

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2003). Good business: Leadership, flow and the making of meaning. Penguin.

Delbecq, A. (1999). Christian spirituality and contemporary business leadership. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 12(4), 345–349. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534819910282180

Dhar, N., Chaturvedi, S. K., & Nandan, D. (2013). Spiritual health, the fourth dimension: A public health perspective. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health, 2(1), 3–5.

Ellison, C. W. (1983). Spiritual well-being: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 11(4), 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/009164718301100406

Fagley, N., & Adler, M. (2012). Appreciation: A spiritual path to finding value and meaning in the workplace. Journal of Management Spirituality & Religion, 9, 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2012.688621

Fisher, J. (2011). The four domains model: Connecting spirituality, health and well-being. Religions, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel2010017

Frost, P. J. (2003). Toxic emotions at work: How compassionate managers handle pain and conflict. Harvard Business Press.

Fry, L. W., Vitucci, S., & Cedillo, M. (2005). Spiritual leadership and army transformation: Theory, measurement, and establishing a baseline. Leadership Quarterly, 16(5), 835–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.07.012

George, S. (2023). Toxicity in the workplace: The silent killer of careers and lives. International Innovation Journal, 1(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7852087

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organizational Behavior & Human Performance, 16(2), 250–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(76)90016-7

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2013). Partial least squares structural equation modeling: Rigorous applications, better results and higher acceptance. Long Range Planning, 46(1–2), 1–12.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing. American Psychologist, 44, 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.44.3.513

Hunsaker, W. D. (2019). Spiritual leadership and job burnout: Mediating effects of employee well-being and life satisfaction. Management Science Letters, 9(8),

1257–1268. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.4.016

Joormann, J. A. (2010). Emotion regulation in depression: Relation to cognitive inhibition. Cognition and Emotion, 24, 281–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930903407948

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

Khatri, P., & Gupta, P. (2017). Workplace spirituality: A predictor of employee wellbeing. Asian Journal of Management, 8, 284. https://doi.org/10.5958/2321-5763.2017.00044.0

McCarthy, G., Almeida, S., & Ahrens, J. (2011). Understanding employee well-being practices in Australian organizations. International Journal of Health, Wellness and Society, 1(1), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.18848/2156-8960/CGP/v01i01/41076

Mendes, F., & Stander, M. (2011). Positive organisation: The role of leader behaviour in work engagement and retention. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 37(1), https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v37i1.900

Moberg, D. O. (1984). Subjective measures of spiritual well-being. Review of Religious Research, 25(4), 351.

Nielsen, K., Yarker, J., Randall, R., & Munir, F. (2009). The mediating effects of team and self-efficacy on the relationship between transformational leadership, and job satisfaction and psychological well-being in healthcare professionals: A cross-sectional questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(9), 1236–1244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.03.001

Paloutzian, R. F., & Ellison, C. W. (1982). Loneliness, spiritual well-being and the quality of life. In L. A. Peplau & D. Perlman (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy (pp. 224–237). Wiley.

Park, C. L. (2017). Spiritual well-being after trauma: Correlates with appraisals, coping, and psychological adjustment. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 45(4), 297–307.

Pawar, B. (2016). Workplace spirituality and employee well-being: An empirical examination. Employee Relations, 38, 975–994. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-11-2015-0215

Rasool, S. F. (2021). How toxic workplace environment effects the employee engagement: The mediating role of organizational support and employee wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,, 18, 2294.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6),

1069–1081.

Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263

Ryff, C. D. (2018). Eudaimonic well-being: Highlights from 25 years of inquiry. In K. Shigemasu, S. Kuwano, T. Sato, & T. Matsuzawa (Eds.), Diversity in harmony - Insights from psychology: Proceedings of the 31st International Congress of Psychology (pp. 375–395). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119362081.ch20

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 9(1), 13–39.

Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behaviour. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190701763982

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Seppälä, P., Harju, L., & Hakanen, J. J. (2020). Interactions of approach and avoidance job crafting and work engagement: A comparison between employees affected and not affected by organizational changes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239084

Spreitzer, G. M., Kizilos, M. A., & Nason, S. W. (1997). A dimensional analysis of the relationship between psychological empowerment and effectiveness, satisfaction, and strain. Journal of Management, 23(5), 679–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(97)90021-0

Su, J. A., Weng, H. H., Tsang, H. Y., & Wu, J. L. (2009). Mental health and quality of life among doctors, nurses and other hospital staff. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 25(5), 423–430.

Su, R., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). The development and validation of the comprehensive inventory of thriving (CIT) and the brief inventory of thriving (BIT). Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 6(3), 251–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12027

Truss, C., Shantz, A., Soane, E., Alfes, K., & Delbridge, R. (2013). Employee engagement, organisational performance, and individual well-being: Exploring the evidence, developing the theory. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(14), 2657–2669.

Yang, F., Liu, J., Wang, Z., & Zhang, Y. (2019). Feeling energized: A multi-level model of spiritual leadership, leader integrity, relational energy, and job performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 983–997. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3713-1

About the Author

Ishani Chakraborty is a research scholar at the Faculty of Management Studies and Research, Aligarh Muslim University. She is also working with S. P. Mandali’s Prin. L. N. Welingkar Institute of Management Development and Research. She has published several case studies in reputed journals in national and international categories. Leadership, ethics and sustainability are her areas of interest. Besides her academic career, she considers herself a ‘storyteller’. She believes in holistic education and is happily an eternal learner. E-mail: cishani2020@gmail.com

Saboohi Nasim, Faculty of Management Studies and Research, Aligarh Muslim University, is a well-recognised professor and mentor in the business management stream. Her doctoral research has been in the area of strategic management and e-governance from the Department of Management Studies, IIT Delhi. She has been awarded the National Doctoral Fellowship and also has to her credit the Cummin’s Best Case Award. Her research interest has been in the areas of strategic management, change management, organisation management and e-Governance. E-mail: saboohinasim@gmail.com