1 C. U. Shah University, Surendranagar, Gujarat, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www. creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The promotion of employee well-being and performance is one of the key goals of organisations after COVID-19. Nonetheless, the current economic crisis tyrannises this goal, cruelly jeopardising the sustainability of prior decades’ well- being and performance. It is acknowledged that stress is unavoidable and if not managed properly, can have a negative impact on teachers’ health and well-being. In the current research, responses were collected from 512 university teachers to understand the challenges they are facing and the results were analysed with the help of ‘principal component analysis’. Results revealed that major factors contributing to the feelings of being stressed are sense of insecurity due to poor skills, unable to meet deadlines, lack of clarity, violating formal procedures, uninteresting work, poor quality due to heavy workload, fear of losing job, and lack of training and preparation. The symptoms and dangers of stress can be reduced by raising awareness, taking remedial action and engaging in appropriate stress-reduction activities.

Mental health and well-being, organisational sustainability, occupational stress, university teachers

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations serve as a ‘common blueprint’ for global action in order to achieve a more just, equitable and sustainable world for all by the year 2030. SDG 3 specially describes Mental health and well-being (MHW) which is crucial for achieving sustainable development. Mental health issues account for over 13% of the worldwide disease burden, affect up to 10% of people at any given moment during their lives, and account for more than a quarter of the years people live with disability globally.

We thrive on performance, competitiveness and perfection in today’s world, which leads to an alarming condition of ever-increasing stress levels. Stress has existed since the dawn of time, yet its toll is now greater than ever. Because we do not examine and evaluate stress closely, we frequently underestimate the harm it can cause in our lives. Understanding the existing state of employees’ health and well-being, as well as internal and external stakeholders’ expectations, is a crucial step. The epidemic has prompted several significant modifications in company policy that promote employee health. The current study presents empirical data and information on stress and work–life balance among university professors. It detects main stressors influencing the work environment and family environment, as well as measures to reduce stressful feelings.

Literature Review

A happy workforce is more productive than an unhappy one. In order to ensure that employees are healthy and fine, it is essential to identify the stressors that contribute towards the disturbances among the workers. In their study, Doss et al. (2018) determined and compared the levels of occupational stress and professional burnout among 220 teachers. Various tests were used to arrive at the conclusion that stress and burnout levels differ considerably between male and female teachers. Teacher burnout was predicted by poor working conditions, time pressures and student misconduct. Banerjee and Mehta (2016) in their study revealed that teaching stress leads to job avoidance, whereas work overload stress and poor interpersonal relationships lead to job dissatisfaction. Offering social support and implementing better coping strategies are so much correlated to good performance among the teachers. Social support factors such as instrument support, emotional support and co-workers contribute to the well-being of an individual.

It is also essential to frame good work–life policies to help the employees to maintain a good work–life balance. Hasan and Teng (2017) suggested that work– life policies should be developed to ensure employee engagement and create a healthy work–life balance. According to Agha et al. (2017), work interference with personal life and personal life interference has a negative association with job satisfaction, while work and personal life enhancement have a good relationship with job satisfaction. Rajkumar (2016) studied the factors of job stress among teachers by reviewing various literatures. Stress is prevalent at a high level among faculty members, according to the analysis of many sources, and hence actions should be taken to control it. The result of the study conducted by Sabherwal et al. (2015) indicates that lack of regular breaks (85%) and long working hours (83%), harassment by managers/staff/students (75%), lack of communication with staff (73%), poor pay prospects (81%) pace and intensity of change (75%), high degree of uncertainty about work cause maximum stress. Kalpana and DhineshBabu (2015) suggested that women’s health should be prioritised by management, who should encourage sports and leisure activities, as well as eating healthy foods and obtaining adequate sleep. Additionally, time should be set aside to deal with family emergencies so that they are able to manage their work and family effectively.

A sustainable workplace tries to foster a culture that actively decreases stress and supports individuals in achieving their full potential. Mayor (2015) has stressed the women’s disadvantage in health and stress. Environmental effects, individual behaviour and genetic factors cause disadvantage to the women’s health. The amount of satisfaction of the teachers has a significant impact on motivation, which is a psychological process. When people are motivated, they are more likely to work harder and act as a driving force within them. Siddique and Farooqi (2014) found a positive relationship between job satisfaction and motivation of university teachers. A study by Desrani (2013) describes various physical and work performance symptoms of stress. It also recognises job insecurity, high demand for performance, technology, workplace culture, personal or family problems, and uncertainty at workplace as various causes of stress.

Assuring that workplace is stress-free and that employees have access to engaging ways of working that suit their preferences is an important part of lowering stress. Saha et al. (2011) suggested that systematic division of workload management policy, adequate delegation of authority, recognition of efforts, training, stress and time management can be the useful measures to overcome stress and promote sustainable workplace. According to Winefield et al. (2003), inadequate financing and resources, work pressure, bad management practices, job insecurity, and insufficient recognition and reward are all key contributors to stress. Saranya and Gokulakrishnan (2013) found a positive association between work–life balance and imbalance in the contexts of depression and psychological stress. When we practise sustainability in our daily lives, it benefits both ourselves and the world, implying that personal well-being and environmental sustainability do not have to be mutually contradictory aims. We can pave the way for a happy future by investigating these effects and what organisations can do to enhance employee well-being and sustainability. Business leaders are becoming increasingly aware of how their workplaces are set up, as well as their responsibility to prevent detrimental effects on people’s health and well-being.

Research Gaps

While it may be difficult to predict the workplace’s future as new technology and trends arise, we can be certain of one thing: The future workplace should encourage our health. Furthermore, given the growing interest in well-being among younger generations, a healthy workplace can be a valuable advantage in attracting and retaining talent.

Although many academics have worked to discover the factors that influence university professors’ health, with the emergence of new technology and increased competition, the factors may change from time to time. With the rising focus on sustainable and healthy workplaces, it is critical to detect the potential sources of issues for university professors and to improve overall well-being. Also due to COVID-19, many individuals suffered from anxiety and depression which led to multiple problems and hence it was imperative to recognise those challenges and resolve them.

Research Methodology

The deterioration of psychological well-being has important consequences in economic terms (Robertson & Cooper, 2010). Teachers play a crucial role in the teaching-learning process. However, as instructors are expected to fulfil various jobs at the institutional level, stress has become one of the most important issues in today’s world. The present study highlights the sources of stress which affect the psychological well-being of the teachers. The data collection was done through primary and secondary sources. Past literatures were referred to identify the factors that have a significant influence on the stress levels among the university teachers. With the help of a structured questionnaire with 5-point Likert scale, opinions of respondents were taken. The variables selected in the present study in order to recognise the opinions of the respondents regarding occupational stress are purely descriptive in nature. The Occupational Stress Index (OSI) standardised by Srivastava and Singh (1984), Teacher’s Stress Inventory developed by Dr M. J. Fiman (1984), and The Scale of Occupational Stress by the Bristol Stress and Health at Work Study were reviewed to identify the variables that assess the occupational stress among the university teachers.

The researcher found the primary components that contributed to the feelings that created stressful situations and had an impact on the work–life balance of the participants. The occupational stress was measured through variables covering workload, unclear job role, group pressure, role conflict, responsibility for others, underutilisation of abilities, participation in decision-making, relationship with colleagues, resource inadequacy, working condition, inequity of pay, job security, discipline, management support and intrinsic insufficiency. The replies were gathered from 512 university professors in order to understand how they felt about their jobs.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to extract the maximum common variance from all the variables used for the study. There were a few factors that never contributed to feelings of stress, some factors that led to rare feelings of stress, situations that occasionally contributed to those feelings and a few factors that mostly contributed to stress out of 33 phrases that aimed to identify the feelings of university teachers towards their job.

Findings

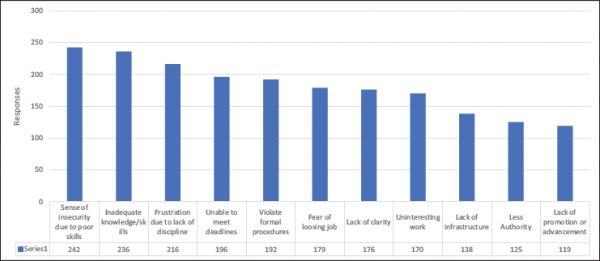

Following the preliminary investigation, the factors that contributed to stress sensations were identified as never, seldom, occasionally, mostly and always. The factors that mostly contribute to stress are a major concern from the management’s perspective. Figure 1 shows the factors.

A sense of insecurity in the workplace due to lack of skills generates stress for 242 university professors, followed by 236 responses indicating insufficient knowledge or skill. Frustration stemming from a lack of discipline is followed by deadlines, a lack of clarity in one’s professional function, uninteresting work, a lack of infrastructure, formal procedures, fear of losing one’s job, a lack of authority and a lack of promotion.

PCA is being utilised to find the causes of stress with the highest loadings in this study. In order to assess the appropriateness of PCA, Kaiser–Mayer–Olkin (KMO) Test is performed.

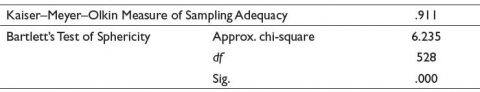

As seen in Table 1, the measure of sample adequacy is 0.911 which is higher than the average value of 0.7 and hence the available data are considered reliable for PCA. The PCA was carried out to explore the underlying factors associated with 33 items. Table 2 explains the total variance through PCA.

Table 1. Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy.

Source: SPSS 16 output based on primary data.

Figure 1. Factors that Mostly Contribute to the Stress.

Source: Output based on primary data.

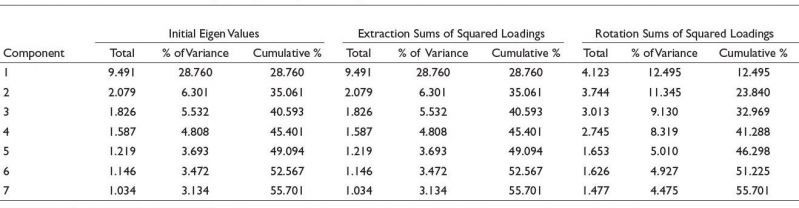

Table 2. Total Variance Extracted through Principal Component Analysis.

Source: SPSS 16 output based on primary data.

Note: Extraction method: Principal component analysis.

Seven factors are extracted from the analysis along with their eigenvalues, and the per cent of variance attributable to each factor. The first factor is responsible for 28.76% of the variance, while the second factor is responsible for 6.30%, the third factor is responsible for 5.53%, the fourth factor is responsible for 4.81%, the fifth factor is responsible for 3.69%, the sixth factor is responsible for 3.47% and the seventh factor is responsible for 3.13%. The total percentage of the factors extracted is 55.701%.

The first component with highest loadings consists of eight factors. They are sense of insecurity due to poor skills 0.731, unable to meet deadlines 0.689, lack of clarity 0.581, violate formal procedures 0.566, uninteresting work 0.562, poor quality due to heavy workload 0.560, fear of losing job 0.559 and lack of training & preparation 0.509. These factors reveal the professional competence of the university teachers which they are expected to be good at. Lack of these factors or skills affects the competence level of the teachers which increases their feeling of stress.

Discussion

Workplace well-being is critical for cultivating a sense of worth in employees, assuring their engagement and eventually leading to improved levels of productivity and organisational performance. In recent years, having an environmentally friendly and stress-free workplace has moved to the top of the company agenda, and it has become significantly more essential to employees. Sustainable workplaces promote culture that encourages employees for an outstanding performance by extending support and healthy work environment. Many firms have switched to remote working as a rule rather than an exception in a world where COVID-19 keeps us on our toes.

The present study intended to identify the factors contributing to stress among the university teachers. The availability of material online has increased the body of knowledge, posing a challenge to faculty members in disseminating the information in a meaningful manner so that students are motivated to learn. The factors recognised among the university teachers that contributed to a sense of uneasiness were the fear of losing employment, lack of clarity, uninteresting work, lack of infrastructure, less authority and lack of promotion or advancement chances.

PCA was performed to recognise the major factors. Insecurity owing to weak abilities, inability to fulfil deadlines, lack of clarity, breaching formal processes due to group pressure, uninteresting work, low quality due to heavy workload, fear of losing job, and lack of training and preparation are among the variables included. The component accounted for 55.71%variance in overall stress. The results were supported by the study conducted by Sliškovic & Seršic (2011) who concluded that the biggest cause of teaching stress has been found as a focus on quantity of work rather than quality improvement. High amount of work, issues and arguments and demands from co-workers and supervisors, insufficient resources for suitable performance, insufficient skills to the demands of their role, and a sense of underutilisation were found by Ahmdy et al. (2007).

Conclusion

Well-being is inextricably linked to a company’s overall sustainability strategy and mission. It is also acknowledged that stress is unavoidable and, if not managed properly, can have a negative impact on teachers’ health and well-being. The role of educators, their obligations and teaching activities are all influenced by the fast-changing educational process, which causes stress and affects an individual’s psychological well-being. Ateacher’s job description includes extra responsibilities such as administrator, motivator, counsellor and mentor. Teaching professionals are increasingly confronted with conflicting conditions at work and at home as a result of their performance in these professions. The study analysed the components at the workplace that contribute to stress and create an imbalance between work and family in order to gain a meaningful understanding of the challenges encountered by educators.

The symptoms and dangers of stress can be reduced by raising awareness, taking remedial action and engaging in appropriate stress-reduction activities. Researchers, academics, educational policymakers, administrators, educational institutions, counsellors and teachers can use the data gathered and the conclusions produced by the researcher to guide future orientations.

Managerial Implication

The study’s findings revealed a number of implications that might be implemented in order to create a stress-free working environment and attain work–life balance. Teachers felt stressed due to lack of adequate knowledge and skills to justify the roles & responsibilities and it was suggested to conduct faculty development programmes to cover the aspects such as effective communication skills, research skills, classroom discipline and innovative teaching pedagogy. In order to help with the issue of over workload, it was suggested to distribute the workload methodically. It was suggested to execute strategies like setting annual goals with the help of dean or director and develop a support system and network in order to have more clarity about the role and set the priorities. To overcome the fear of losing job, teachers should be guided with in-lesson preparation and post-lesson activity. Job discontent is caused by lower pay compared to work performance, and if teachers are unhappy, students will be unhappy as well. As a result, regular recognition of work performed in monetary or non-monetary elements, as well as higher promotion possibilities, might be beneficial. As the level of competitiveness and pressure to work as a team rises, official procedures are being broken. To overcome such troubles, a list of standards and expectations should be drafted, and team-building exercises should be done to foster teacher cooperation.

Limitation

The research is hampered by the quality of composition of the sample under investigation. The study is limited to public and private university teachers only and other categories are not examined. Although the sample size is adequate, larger population could be covered.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Agha, K., Azmi, F. T., & Irfan, A. (2017). Work–Life Balance and Job Satisfaction: An Empirical study Focusing on Higher Education Teachers in Oman. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 7(3), 164.

Ahmdy, S., Changiz, T., Masiello, I., & Brommels, M. (2007). Organizational role stress among medical school faculty in Iran: Dealing with role conflict. BMC Medical Education, 7(1), 1–10.

Banerjee, S., & Mehta, P. (2016). Determining the antecedents of job stress and their impact on job performance: A study among faculty members. IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(2), 7.

Desrani, H. (2013). Occupational stress and management policies. Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(6), 15–22.

Doss, C. A. V., Rachel, J. J., AbuMadini, M. S., & Sakthivel, M. (2018). A 258 com- parative study to determine the occupational stress level and professional burnout in special school teachers working in private and government schools. Global Journal of Health Science, 10(3), 42.

Hasan, N. A. B. B., & Teng, L. S. (2017). Work-life balance and job satisfaction among working adults in Malaysia: The role of gender and race as moderators. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 5(1), 18–24.

Kalpana, S., & DhineshBabu, S. (2015). A study on work–life balance among women mar- ried college teachers in Trichy district. Shanlax International Journal of Management, 3(2), 57–69. https://www.shanlax.com/wp-content/uploads/SIJ_Management_V3_ N2_006.pdf

Mayor, E. (2015). Gender roles and traits in stress and health. Name: Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 779.

Rajkumar, A. D. (2016). Job stress among teaching faculty: A review. International Journal of Applied Engineering Research, 11(2), 1322–1324.

Robertson, I. T., & Cooper, C. L. (2010). Full engagement: The integration of employee engagement and psychological well-being. Leadership Organization Development Journal, 31(4), 324–336.

Sabherwal, N., Ahuja, D., George, M., & Handa, A. (2015). A study on occupational stress among faculty members in Higher Education Institutions in Pune. SIMS Journal of Management Research, 1, 18–23.

Saha, D., Sinha, R., & Bhavsar, K. (2011). Understanding job stress among healthcare staff. The Online Journal of Health and Allied Sciences, 10(1), 6.

Saranya, S., & Gokulakrishnan, A. (2013). Work–life balance among women academician with reference to colleges in Chennai. Asian Journal of Managerial Science, 2(2), 21–29.

Siddique, U., & Farooqi, Y. A. (2014). Investigating the relationship between occupational stress, motivation and job satisfaction among university teachers (A case of University of Gujrat). International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 3(4), 36–46.

Sliškovic, A., & Seršc, D. (2011). Work stress among University teachers: Gender and position differences. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, 62(4) 299–307. Srivastava, A. K., & Singh, A. P. (1984). The occupational stress index. Manavaigyanic Parikshan Sansthan.

Winefield, A. H., Gillespie, N., Stough, C., Dua, J., Hapuarachchi, J., & Boyd, C. (2003). Occupational stress in Australian university staff: Results from a national survey. International Journal of Stress Management, 10(1), 51.